FF Discount code: MUSIC

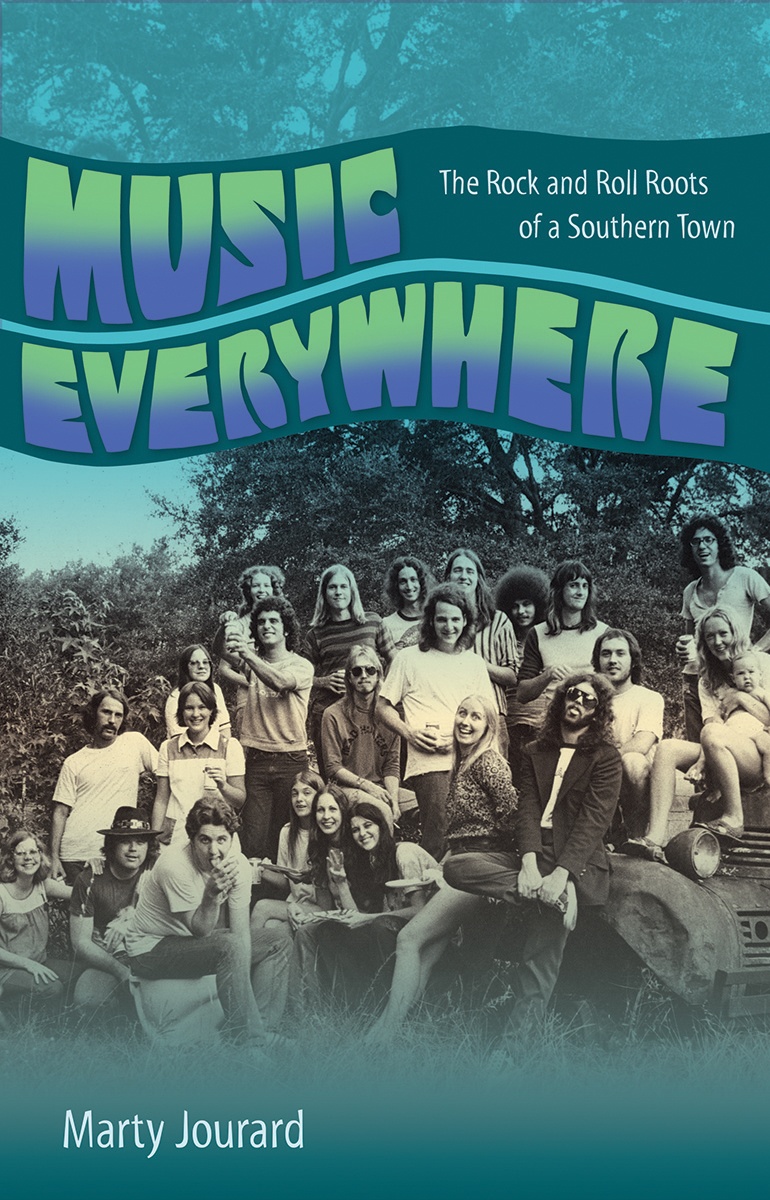

Many American college towns have their own story to tell when it comes to their rock and roll roots, but Gainesville’s story is unique: dozens of resident musicians launched into national prominence, eight inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and a steady stream of major acts rolling through on a regular basis. This excerpt from Music Everywhere has been reprinted with permission from the University Press of Florida as part of our series of excerpts highlighting the work of Florida literary magazines and publishers.

See You Later, Alligator

The year 1955 is described by many music historians as the year rock and roll was born. Among the many pop records released that summer were Chuck Berry’s first single, “Maybellene,” Little Richard’s “Tutti Frutti,” Fats Domino’s “Ain’t That a Shame,” and Bill Haley and His Comets’ “Rock Around the Clock,” a song that spent eight weeks at the top of the Billboard charts and helped jumpstart the rise of rock and roll.

That same year a Gainesville musician named Tommy Durden wrote a song inspired by a newspaper article after his eye had been drawn to a Miami Herald photo with the headline, “Do You Know This Man?” The suicide victim, discovered in his Miami hotel room, had left the simplest of notes: “I walk a lonely street.” Durden was struck with the blues-drenched image of a man walking a lonely street; the following weekend he drove to Jacksonville for a weekly performance on a local television show, where afterward he met with his occasional songwriting partner, Mae Boren Axton. Together Durden and Axton finished his half-written lyric, adding a hotel at the end of the lonely street—a Heartbreak Hotel—and recorded a demo of the tune with local vocalist Glenn Reeves. Later that month, Axton attended a disc jockey convention in Nashville and played the demo for another attendee—Elvis Presley, who was wildly enthusiastic about the song and quickly recorded it, taking care to emulate the vocal phrasing and singing style on the demo, which ironically was Reeves doing his best Elvis imitation. Tommy Durden later said, “Elvis was even breathing in the same places that Glenn did on the dub.” “Heartbreak Hotel” became Elvis’s first RCA release, held the top chart position for eight weeks, and was the best-selling single of 1956.

Home Sweet Home

In 1955, among the thirty thousand or so citizens of Gainesville, Florida, there lived four young boys whose future involvement with music was anticipated by absolutely no one—they were children, and rock and roll was even younger than they were. Several decades later they would share a singular musical honor, but in the heart of the fifties, the only thing they shared in common was living a few miles apart from one another underneath the big hot Florida sun.

In the northwest part of the city lived Otie and Talitha Stills and their son, Stephen, eight years old and in second grade at Sidney Lanier Elementary School. The Stills family had moved from Texas, New Orleans, and Illinois before arriving in Gainesville in the early fifties. “My father was basically one of those entrepreneur types, that would just start up stuff, make a bunch of money, then get bored,” Stills recalled. “We didn’t get to the beach, but we stopped in Gainesville. He thought it was the prettiest place he ever saw.”

Four blocks to the south of the Stills’s house was the home of Benmont Tench Jr., his wife, Catherine, and their two children, Catherine and Benmont. In 1867, Civil War veteran Major John W. Tench of Newnan, Georgia, traveled to Gainesville to visit his wife’s uncle. He found the city to his liking and moved there, where one of his sons, Benmont, had a son, Benmont Jr., in 1919, whose son Benmont Tench III was a fourth-generation Gainesville resident.

Three miles northeast lived Benmont’s future bandmate, Tommy, the four-year-old son of Earl and Katherine Petty. The Petty patriarch, William “Pulpwood” Petty (1883–1956), was originally from Waycross, Georgia, but left the state in the early 1920s, a few years after marrying a full-blooded Cherokee Indian and determining that the locals were less than tolerant of his mixed-race marriage. He and his wife and children traveled across the border to north Florida, where in Gainesville his grandson Thomas Earl Petty was born in 1950.

Three blocks west of the Petty house lived Charles and Doris Felder with their two sons: twelve-year-old Jerry and seven-year-old Donny. Donny was a typical southern boy, often found riding his bike in the neighborhood, collecting empty two-cent Coke bottles. After cashing them in at the local drugstore, he would treat himself to an RC Cola and a MoonPie. Don’s grandfather, Henry Hampton Felder, was born in 1877 and lived in North Carolina. As a boy, he had decided the state was too cold and left, riding a mule south on dirt trails through the mountains until he arrived at a midland Florida settlement called Hogtown, where he dismounted, spent the night, got up the next morning, looked at the mule, and decided, “I’m not getting back on that thing. I’m just going to live here.” His son Charles was Don Felder’s father. They came, and they stayed.

What brought all these folks to Gainesville in the mid-1950s?

Gainesville did. For many years, the masthead of the Gainesville Daily Sun included this simple motto: We Like It Here. It was a small, livable college town where people with diverse backgrounds came together from all across the country.

There was something comfortable about Gainesville. Ninety miles from the Georgia border and located almost exactly between the Atlantic and Gulf coasts, Gainesville was easily discovered by travelers headed south. If you were driving south on US 441 through the middle of the state, you couldn’t miss it. For some visitors it was too pretty a place to forget. People liked it, and stayed.

Sleepy Time Down South

In the years that preceded the sudden growth in its live music scene, Gainesville was more conservative and relatively idyllic. Gainesville in the early sixties had a population of just over fifty thousand. The passenger train no longer ran down the middle of Main Street—that ended in 1948—but you could still catch the train down at the depot near University Avenue and NW 6th Street.

Prior to 1964, Alachua was a “dry” county, and you could buy liquor only by the drink at a restaurant. The nearest source of liquor by the bottle was Ruby’s Restaurant and Package Store, just over the Marion County line, south of Gainesville.

The Soap Box Derby, sponsored by the Boys’ Club, was a major annual event, as were the annual Homecoming Parade down University Avenue and Gator Growl, the largest student-run pep rally in the world. Colonel Harlan Sanders, founder of the Kentucky Fried Chicken restaurant chain, was the grand marshal one year, leading the parade in his trademark white suit, waving to the crowd.

In the summer the county health department dispatched a flatbed truck that slowly drove through neighborhoods in the evening, spraying a white mist of vaporized kerosene to control the mosquito population; kids would gleefully run through the fog and follow the truck down the street. After school, children would play outside until dark. In certain neighborhoods each mother had a handbell she would shake to signal when it was dinnertime; you knew the sound of your bell. Children often ran around barefoot. Some older kids would go frog-gigging at night and return home with a bucket of bullfrogs. Rattlesnake Creek ran through part of the city, and younger kids, including this writer, would wade through the shallow water and routinely find and collect ten-million-year-old shark teeth and fossilized shells. Deep pools in the creek held crayfish, water snakes, minnows, and softshell and snapping turtles. Dragonflies hovered about, and the unique sound of cicadas filled the air as you waded about: you were a part of the nature that surrounded you. Gainesville and nature were inseparable.

There was another less idyllic side to life in the early sixties. The Cold War was in full force; the threat of atomic bomb annihilation was always in the back of our minds; and AM radio had periodic tests of the Emergency Broadcast System, a fifteen-second high-pitched tone. Radio dials had a small triangle symbol near the low end; that was where you tuned in if there was a civic emergency: an atomic bomb certainly qualified as one. Public service announcements on television explained what to do in the event of an atomic bomb. Fallout shelters were in vogue, and some families actually had one, buried in the back yard, a bulge in the lawn topped with a ventilation pipe and metal hatch the only sign of its presence. Communists were seen as wanting to take over the world. The Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 brought home the fact that Soviet nuclear missiles were aimed at the United States ninety miles away from . . . Florida, the very state where we lived. Fear of the atomic bomb and Communism was a continuous presence in our lives in the late fifties and early sixties.

Like southern cities of the time, Gainesville had a black population firmly separated from whites in all social settings: segregated schools, restaurants, restrooms, and drinking fountains. The College Inn, a popular student cafeteria, displayed in its window a neon sign with a simple, direct phrase in light blue cursive: “White Only.” Tradition died hard in the Deep South. There were two white movie theaters, the Florida and the State; the Rose Theater for the African-American community; and two drive-in movie theaters, the Gainesville and the Suburbia. A Saturday matinee at the Florida cost thirty-five cents, where you could watch cartoons, an episode of an adventure serial, and a feature movie such as Hey, Let’s Twist.

Gainesville’s downtown had the look of another era. Although most of the main city streets were of asphalt, much of the heart of downtown Gainesville was paved in red brick from the turn of the century. A statue of a Confederate soldier stood guard in the courthouse square. A series of horseshoes still embedded in the sidewalk across the street led the curious pedestrian around the corner to a building that was a wagon and buggy shop in the 1880s. City buses were green and white, and the fare was ten cents. Cocolas—that’s what you called them, or an “I-scold-Coke”—were also a dime, candy was a penny, a pack of Juicy Fruit gum was a nickel, comic books were twelve cents, and gas was sometimes as low as a quarter a gallon. A uniformed service-station attendant would fill the tank, check the oil, wash the windshield, check and inflate the tires, then hand you a six-pack of Coke as a bonus for filling up.

Midland Florida’s subtropical climate made Gainesville summers exceedingly hot and humid, with little relief even at night, and at times it rained daily, usually around 2:30 p.m., after all the rain from the previous day had evaporated upward and formed new rain clouds. Spanish moss hung languidly from the widely spread limbs of ancient live oaks. Markets and roadside stands sold watermelons for twenty cents. The Tackle Box out on Hawthorne Road sold fishing supplies and live bait and displayed uncut bamboo fishing poles and raw sugar canes stalks that you cut into serving sizes and chewed. Boiled peanuts were a popular snack. You were living in the Deep South.

Despite the languorous atmosphere, or perhaps because of it, the youth of Gainesville were always seeking an outlet for all that youthful energy. Gregg Allman describes this feeling in his memoir, My Cross to Bear: “back then we had so much energy, so much drive, and so much want-to.” For some kids this energy, drive, and want-to became focused on playing music.

The People Factor

Much of life consists of countless interactions with other people, a multitude of daily encounters that in most cases have no long-range significance or consequence. However, when those of an artistic temperament interact with one another, a creative synergy occurs, with results bigger than the sum of their parts. Gainesville’s overall cultural environment eventually became a breeding ground for musicians and rock bands during the sixties and seventies. A perennial influx of new college students every year and the exit of those graduating created a constant sense of ongoing movement and new possibilities for musical collaboration. When musicians hooked up with other musicians sharing similar interests in an environment conducive to creativity, good things would happen.