In the top right corner of my second computer monitor, I kept a livestream open. It was a gangly sight – a sticks and twigs in a giant brown mottled mass, dappled with white bird shit around the edges. The centerpiece—the reason I watched—preened the dark feathers of her chest and wings with her golden raptor beak. Her mate landed next to her, his white tail feathers fanned out and yellow talons flexing before he nuzzled his white head on the branches. He approached her, she lifted herself up to stand, and both eagles had my full attention. I ran my palm over my growing stomach as I watched the parents tend to two ivory eggs and thought I felt a stirring. The eagles nudged one egg this way, poked the other one another way, and finally the momma settled back down while her mate flitted offscreen again.

A colleague stopped at my cubicle, resting her elbow on the top of one of its sides. “Still no babies?” she asked.

“Still waiting,” I said, twiddling the new bands on my left ring finger.

•

Reuters reports that children and women crossing into the United States at the southern border with Mexico may be separated if they do not enter at an official port of entry.

•

A killdeer squawks and does her broken-wing dance as my now-one-year-old leads me by the hand toward the swing set. The bird, beautiful and brown with black and white collars around her neck and breast, makes herself a distracting flutter not ten feet away from us. I stop walking and kneel, pulling my toddler son against me, and point the bird out to him. We have a pet parrotlet at home, so his face lights up in recognition. He points to the bird and shouts, “Kitty!”

“No, baby,” I say, as I’ve said countless times before. “Birdie.” I enunciate the B.

“Kitty,” he insists.

I’ve never seen a killdeer in the wild before, and not knowing her dance is a ruse, I worry she’s genuinely hurt, flapping about on the ground like that. It’s a cold, blustery day in early Florida springtime, so I figure I can slip off my jacket and trap her in it before bringing her to the wildlife sanctuary. I sit my son in the bucket baby swing nearby and approach her slowly. My son’s legs, hanging out the holes of the bucket, lightly kick as the bird darts around––seemingly unharmed––then continues her attempts to distract me.

I stop and scan the ground and find what I’ve been missing: four smooth spotted eggs nestled in old mulch, tucked along the side of the divider between the mulch and soil smack in the middle of our neighborhood playground.

“Oh, momma,” I tell the anxious killdeer, “this is a very bad place for your nest.”

•

International law dictates that asylum seekers shall not be penalized due to irregular entry.

•

As newlyweds, my husband and I watched the eagle webcam together when we were both home. The eaglets, now hatched, alternated between sleeping and loudly peeping for food. I pressed my husband’s hand to my belly so he could feel the kicking there. We cooed at the baby birds, their fuzzy grey bodies dwarfed in the mass of twigs and moss in the giant Tulip Poplar tree they called home.

•

With my phone, I snap photos of the playground’s killdeer and her eggs and, ignoring the shitstorm on my feed about the latest outrage on the US-Mexico border, I post the photos to my neighborhood’s Facebook group. With so many tiny sneakered feet that traipse around through this mulch, my post might not be enough to protect this momma and her eggs. With wooden stakes and bright ribbon, perhaps I’ll make a small perimeter for her.

My child makes impatient grunting sounds, requesting I push him in the swing. I oblige.

The mother killdeer stops her dance and returns to sit on her nest. It seems she has decided to tolerate us while my child delights in the pendicular movement of the swing.

•

White House Chief of Staff John Kelly asserts that the mass migration from Central America to the United States via the Mexican border consists primarily of families trying to save their children.

•

Once the eaglets hatched, more of my co-workers kept the nest webcam up on their monitors, and we took to yelling over our cubicle walls when something exciting happened.

“Mr. President is back with a fish!”

“One of the babies is hopping on a branch!”

“Look at how The First Lady nuzzles each eaglet!”

The birds, living in the National Arboretum in Washington, DC, were appropriately named. These eaglets, named Freedom and Liberty, reflected the optimism and patriotism we had for the coming election—what I hoped my unborn child would experience as a US citizen.

•

My son and I bring my husband to see the nest before we take a bike ride. I initiate the outing the second I’m home from work, grateful to shut off NPR’s political commentary on child separation as I pull into the driveway and kill the engine. My husband is swift to retrieve the bicycles while I change my shoes. Soon, all three of us, helmeted and smiling at the sudden warmth in our day, set off on the sidewalk toward the playground. From his perch on my bicycle, our son squeals, “Kitty!” when he sees the bird beneath the swing set.

“Sky kitty,” my husband says.

I don’t bother to correct either of them.

We keep our distance and the killdeer does not do her broken-wing dance for us. Instead, she eyes us quietly while sitting on her eggs.

Two elderly neighbors on a walk with their yorkie make their way toward us. “Be careful with the nest!” they say, pointing next to the swings.

“We aren’t coming any closer,” I respond, pulling my bicycle backwards–out of the walkers’ way and further from the killdeer. We go on our way.

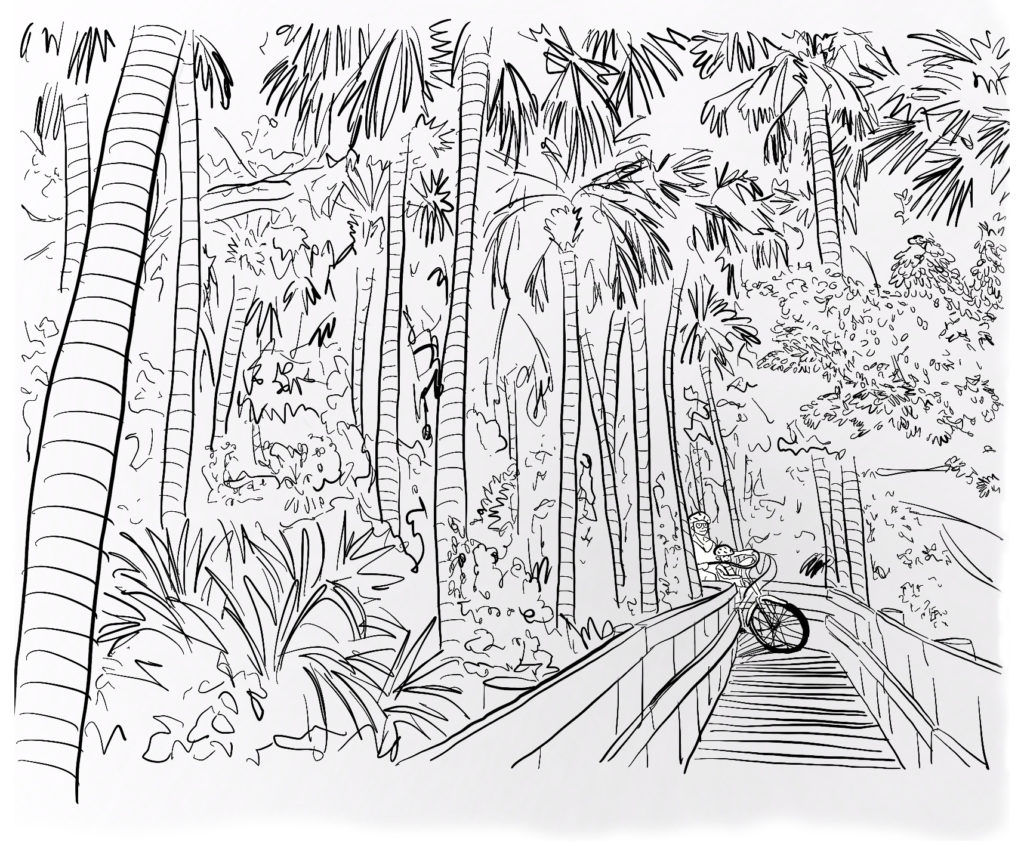

My husband and I take turns leading as we explore the boardwalk trails through the wildlife preserve by our neighborhood.

Our son rides in a special seat affixed to my bike between my seat and handlebars, giving him a front-row view of our adventure through the paved trails in the underbrush, over the muggy swamps, and around the lily-padded retention ponds before we return to the civilized asphalt and cookie cutter houses on stamp-sized lawns. His little toddler helmet makes our son look like a bobble head, lightly bouncing around as we loop our way through the palm-fronded woods, out to sanitized urbanization, and back again.

The alternating dark and light boards of the conservation area’s wooden boardwalk rattle under our bicycle tires like we are playing giant piano keys. At every turn in the narrow boardwalk, my husband and I ring our bike bells.

When the shadows stretch long and the dappled sunlight disappears from our trails, we head home. Watercolors explode from the sky in vibrant shades of fuchsia and chartreuse with the setting sun. I spot the bright shining dot of Venus chasing the sun before we park our bikes in the garage, unstrap our toddler from his perch seat, and hang our helmets on our handlebars. I never make the perimeter for the killdeer mom.

•

The United States’ Attorney General claims their child-separation policies will discourage immigrant parents from crossing the border with their children.

•

The caption under the eagle webcast read, “This is a wild eagle nest and anything can happen. While we hope that two healthy juvenile eagles will end up fledging from the nest this summer, things like sibling rivalry, predators, and natural disaster can affect this eagle family and may be difficult to watch.”

•

My mother-in-law is the Florida flora and fauna expert of the family, so we tell her about the killdeer over dinner one evening.

“They’re supposed to be protected!” she says. “Back when my work had a rock roof,” she points skyward with her fork, “those birds would come and lay eggs there all the time. I guess the rocks were great camouflage.” She takes a bite of her salad. “There was a special group of scientists who set up across the street to watch them one year. Good thing, too.” She pauses for a sip of sweet tea. “Our building manager hated those birds and would go up on the roof and stomp all over the eggs to get them to go away.”

“Oh my God,” I say, eyes wide. My son is sitting in my lap. I run my fingers through his hair as he eats cold French fries from my plate.

“Yup,” my mother-in-law confirms. “He had to stop smashing the eggs because the scientists were watching. I guess someone saw what he was doing and called it in.” She takes another bite of her salad. “Ever since we got the new metal roof, though, the birds haven’t been back.”

•

To be granted asylum in the United States, applicants must have a well-founded fear of persecution or qualify for protection under the United Nations’ Convention Against Torture.

•

While I was pregnant, I sent my husband multiple texts a day with pictures from the eagle webcam. Momma bird with a fish. Daddy bird preening his young. We observed the eaglets sprout awkward adolescent plumage and explore the heavy boughs of their tree home. One bird, more bold than the other, hopped from branch to branch, stretching and flapping its wings while its’ sibling scrutinized the remains of some carcass at the edge of the nest. We marveled at the speed of their growth, and hedged bets on which would fledge first.

•

My son and I return to the playground in early morning to enjoy the swings and check on the eggs and their mother.

“Hi, momma,” I say to the killdeer as I slip my son into the swing. She is fluffed up on her nest and cocks her head as if to consider me with her beady eye. “You’re doing a good job,” I say.

She sits and seems to watch my toddler swing.

My child and I enjoy the shining sun overhead and the brisk breeze ruffling our hair. We count to ten in English and then Spanish, one number for each push on the swing. I say the number and he repeats after me; I merge my push with a squat and soon my thighs are burning.

During a break between sets, I walk closer to the killdeer to check on her eggs. She lets out a panicked peep and flies to the roof of the closest house.

“Oh, momma,” I tell her while slowing down the swing. “I’m sorry I spooked you. Please come back?”

The swing and I stand still, and I watch the killdeer as she paces on the far roof. “Kitty?” my son asks, stretching out his little arm to point toward the nearby roof.

Come back, momma.

A breeze ruffles the palm trees beside us.

The killdeer calls out a long shorebird song and takes flight, flying adjacent to us, over the pond and into the nature preserve.

“Maybe she’s getting food,” I say, lying to myself. I pull the swing way back.

My son giggles in anticipation.

“I hope she’ll come back soon.”

I let go, and the swing arcs toward the nest and its eggs, then away again, my son screeching gleefully.

•

Cocooned in bed, I breastfed my newborn while I watching the election results roll in on my phone.

My husband snored beside us. The map on my phone was not blue enough. I told my baby, “He’s going to win,” and whispered fuck under my breath.

l switched tabs, and pressed “publish” on one of two articles I’d penned earlier in the day. The one where I tried to stay optimistic. I wondered if this administration could be a “survivable event” for my little mixed-race family before I finally drift to sleep.

•

A study by Syracuse University indicates that 98.5 percent of women with children without legal representation were denied asylum in the United States even though they passed their credible fear interviews.

•

In the dead of winter, Florida of course feels like spring time, so we are out again at the swing. I’m twenty pounds lighter than my pre-pregnancy weight and my baby is now fully in toddler mode, two years old with an exploding vocabulary. My son no longer screeches at the swing, but still delights in its movement, a giant grin plastered on his face, and I propel him forward each time he pulls back.

A neighborhood mom and her littles join us.

A child fiddles with his feet while sitting on the other swing. He says, “One time when we were checking on the eggs that used to be here, we noticed there was a hole in two of them, and they were empty.”

I remember, too. The brown splotched eggs smooth and ivory inside. First one cracked. Then two. Then finally all four were empty, then gone. I never did see the killdeer mother after the day she flew from the roof.

“I think snakes got to the eggs,” I say, “because their mom wasn’t around to protect them.”

I didn’t make the perimeter.

“We tried to keep the kids away,” the other mom says, continuing the story. “Those poor eggs; I don’t think they had a chance.”

I swallow hard. A busy playground is not a good place for a nest.