The hair on his head is gone, but his eyebrows still inch across his face like two black caterpillars playing a polite game of chicken. His body may be down for the count, but his face still has it going on. Each day of the week there’s a different colored cap on his head, and I’m proud to say I crocheted each one. Crocheting is a recent conquest for me, one that did not come easily, since my fingers are short and blunt and often feel more like stubby tan pencils than those sensitive personal tools some other women own.

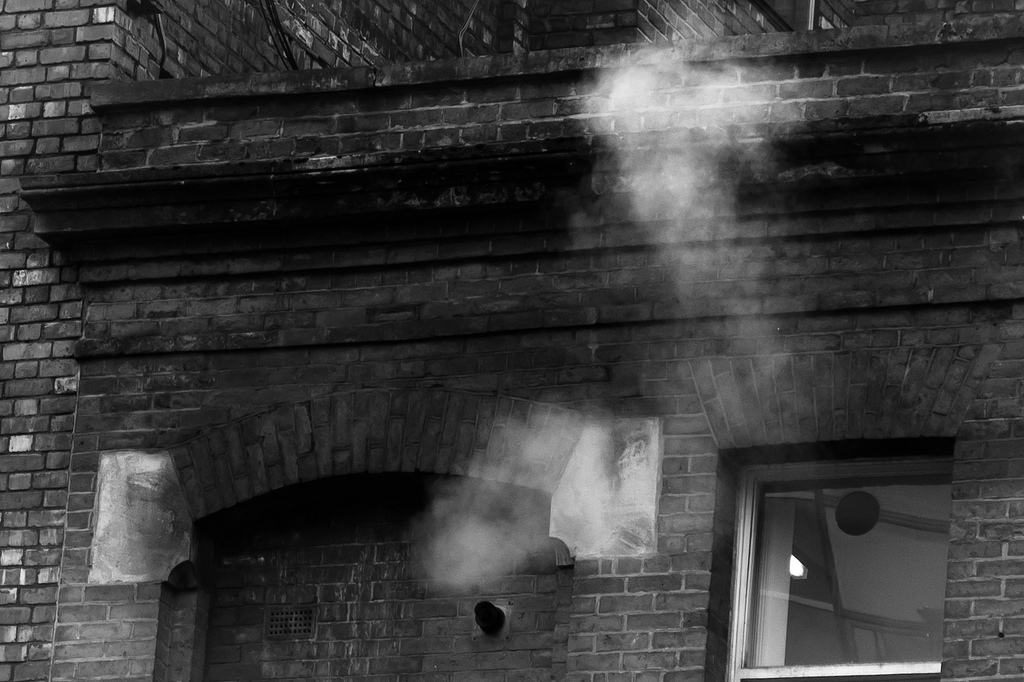

Wind swoops over the house and gives it a bad case of the winter jitters. The boiler sends steam hollering up from the pipes. When I was a kid, when the lights went out for good each night, I used to like this sound of clanging steam. Instead of thinking about how my nose was too wide or my voice was too high or my legs were too short, how I couldn’t dance right and boys didn’t like me, I would float on a calm sea of steam and drift off into dreamland.

Now I hear everything, from the downstairs homebody’s velvety nightly nebulizer treatments to my upstairs neighbors having their clockwork sex every Saturday night at 8:45. Morning prayers and hymns interweave into the fabric of the Sunday air, and not just from the storefront churches, either. The nuns dispense blessings for breakfast, the outreach workers dispense free needles for lunch and holy condoms for dinner. The hookers down the block yell at their pimps on warm summer nights. In the winter, that irregular hiss and snap of the steam is like the building’s breath and I am its brain.

When Adam first moved in, I thought he’d be toast in a couple weeks. I thought each night would be his last. Much later he told me that he asked me only because everyone else had said no. He was, after all, only a friend of a friend, and he asked me via the internet, thinking I’d only turn him down anyway. But I thought he might be a good pretend boyfriend in a bad neighborhood. One hand washes the other, and both hands wash the face.

Sometimes his shallow breath merged with the steam and sometimes, lulled to sleep by exhaustion and the promise of dreams of health, I’d wake with a start and the fear that I’d missed the end of the world.

Instead, he shoulders on. I like that he can’t pronounce the word “soldiers.” It’s one of his delicious flaws. Who wouldn’t prefer a safe body part over a soldier any day of the week? The doctors give him one to six months. He takes seven months, eight months, nine months, rude boy. The house guest who never leaves. Ten months, eleven months, a year. He doesn’t look a lot better, but he doesn’t feel all that much worse.

Our building is perched on a ledge by an old people’s home. If we played kick the can, it would land in a symphony of the aging—shuffling over to benches to enjoy the outdoors, then sagging like a Dali painting into the tops of their walkers. Even if they could move faster, they don’t, as if once they arrive they get handed their walking papers on how to be Old Person, Interrupted. They straggle and gaggle along, a daily tableau for our benefit. Nightly we pull up chairs and check in on cancer, stroke, heart disease, asthma, dehydration, imbalance. Ambulances come and go while survivors blather about birth and the inevitable downpour of death.

No one else is allowed to know what Adam has, by his own dictum. He may have little strength left, but he is a kingmaker in his own little fiefdom, and I don’t dare cross him for fear of what chain reaction I might set off. His friends know he is ill. His close friends, the few that he has, suspect that he is very ill, but they don’t know with what.

Instead, he becomes a citizen of the world, because it is easier to deal with distance. He gets emails every day from intimates he has never met, who long to establish a handhold on his heartstrings. “My dear,” begins one from a Rev. G. Brown, casting off concerns with gender. “You have waited so long to return my letter,” sighs another, from a Mrs. CeeCee Thomas. They are like voices from the near past, emotional versions of tag-you’re-it that have daisy-chained across continents to touch him to the very core, here as he inches ever closer to death.

Before we go to an appointment, I prepare a list of questions in my head, then I talk myself down. When you’re sitting in the waiting room of death, is it tempting fate to come prepared? If I ask the obvious and it’s finally answered, am I sealing his fate? I barely knew Adam before he moved in. It was an impulsive offer, really, the way you’d take in a stray dog off the street till its real owner comes along. After all, he thought he didn’t have long and it seemed like the right thing to do after he lost his job and his girlfriend kicked him out. Perhaps it would return to me in karma. The first month we treated each other like polite familiars who couldn’t quite place the context of our meeting. By the third month he was the first man who knew that my mother had abandoned my father when my twin brother and I were six. By the fifth month Adam knew that my brother had died of leukemia when I was 10. By the eighth month we talked about why we would never consummate our relationship. By the twelfth month I’d known Adam since God was a boy, and I didn’t tell him I was pregnant.

Shoes? Check. Or more like his comfy leather bedroom slippers that he prefers to actual shoes these days, and he justifies this aberration as he does most other things with his cancer. “I’ve earned it,” he claims. Pajamas all day instead of getting dressed? “I’ve earned it,” he’ll insist, flushed and flawed. Nutella fingerprinted out of the jar for breakfast instead of something healthier and anti-carcinogenic, something with—say—kale? “I think I’ve earned it, don’t you?” he’ll say, in all earnestness, not a hint of irony in his voice. He’s got on the hat that I made to keep his bald head warm, a flannel shirt scarecrowed across his bony shoulders, and some thick grey corduroy pants that promote the illusion of body fat. Even if it’s warm outside his body feels cold, like a post-death geothermal chill is reaching out to give him a little taste of what’s to come when the earth finally closes its suffocating fist around him one last time.

I stand outside to try to flag down a cab in the cold while he frets inside the foyer, kidney cancer writ large in new letters from his sorry slump to the expression of defeat on his face. Each day the disease breaks down more barriers from inside to out. Sounds of TV music from dramatic foreign daytime shows spill into each other, cascading out the windows and onto me like a wave of public dreaming. If only this dream had a happy TV ending. But today there are no cabs for hire. We end up taking the bus.

Adam wants privacy at his appointment, but doesn’t tell me till we arrive at the hospital. I wait in the sad crowded hospital coffee shop, wondering what secrets he is shielding me from. I wasn’t prepared to wait, so I have no way to entertain myself but to look at people who don’t want to be watched. If there’s a theme, it’s older men with toothpick legs and potbellied pants waiting for someone made temporarily more important by catastrophe or disease. Are they all cowards who can’t go to their female relatives’ appointments? Many are lulled to sleep by fear, arms at the ready for delayed hugs and lips tensed to deliver soothing words. Others vigorously sleeptalk, ready to battle an empty enemy built of shadows and rhetoric.

When Adam returns, I am fixated on my threadbare socks and concocting an origin story to explain why I hang onto them the way I do. No longer able to grasp my ankles, they shrug down into my boots. Adam’s prolonged visit has put a strain on my finances, counterintuitively extending the life of everything I touch. One look at his face tells me why he didn’t want me to come. We are still corded to each other through an architecture of obligation and suffering, yet it is morphing slowly but surely into a new kind of family structure.

Cold clamps down on the city. When we finally go outside after bundling up, whether or not we talk about anything of substance, our breath will hover in the air like ghosts of steam.

From his pocket, he pulls out one final printed e-mail from the collective voice of the world, before he leaves it behind: “Dear beloved one in Christ,” he reads, “I am Mrs. Joyce Hernandez from Fredonia, New York, United States of America but presently in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. I am 69 years old, I am deaf, I don’t hear and I’m suffering from a long-time cancer of the breast. From all indications my condition is really deteriorating, and Doctor Kelly Silver has courageously advised me that I may not live beyond the next two months. I was brought up in a motherless babies home, and I was married to my late husband Johnson Hernandez for twenty years but I remain childless.

“My husband and I are true Christians, he worked as a contractor and got Coca Cola shares here, but quite unfortunately, he died in a fire. He was burnt to ashes, none of his body was ever found. Since his death I decided not to re-marry and because of my bad stage of health, I sold all our belongings and deposited the total sum of $6.8 million U.S. with a bank in Flushing, New York and all our jewelries, diamonds and golds with a security company.

“My dearest beloved one in Christ, can I trust you to distribute our life earnings to the Motherless Homes and Churches and Haiti suffering people? Yours most truly, Mrs. Joyce Hernandez.”

“Imagine,” Adam says to me as the useless paper flutters to the ground. “Just imagine, working as a contractor and earning $6.8 million dollars in Coca Cola shares, jewelries, diamonds and ‘golds.’ Imagine reaching out to a total stranger via the internet to find orphans for your largesse. Why, some cynical people might say it’s almost too good to be true. Or they might grasp onto this as the only answer to their prayers.”

“Imagine that,” I say. “Imagine how desperate some people might be.” The steam ghosts tag along with us as if they are eavesdropping on our conversation.

We walk in the cold for twenty-four blocks, oblivious to the falling temperature and the impending storm. Adam is more energetic than I’ve seen him in a long time. There’s even a bit of a lilt to his step. I almost have to run to keep up, my socks slipping uncomfortably down around my heels as the snow starts to fall.

My throat is clogged with words that I’m afraid will sound wrong when I try to string them together. The magical pink twilight makes Adam’s fragile profile seem as steady as a statue.

Time like a virus will spread stealthily and efficiently throughout Adam’s remaining days and nights, infecting his health by snatching seconds, minutes, hours. I hurry to catch up to his future, my mind a mist of what I might have done. Then the mist clears and I remember what I was going to say.

______

Photo credit: Ineedagoodname / Foter / CC BY-ND