The Rusalki wait outside my window every night. White lips, grotesque smiles, green hair streaming with silver fish and lily pads. It’s like being in an aquarium. The Rusalki point and jeer through the glass. They tap on the frosted panes with icicle fingernails. Pretty little thing, they whisper, come outside so we can see you better. I pull a quilt over my face, though I still hear them singing, We choose you, over and over. Their voices sound like creaking lake ice.

“Nonsense,” says Babci, as we drink our morning tea and look out at the powdered white landscape. Babci is from the old world. She resembles a withered parsnip. She is rooted to her surroundings in a way I can’t quite understand. Her feet are heavy. Her skirts are voluminous. Even her white hair grows thick and long, as if determined to plant itself into the ground.

“Silly superstitions,” she says, as she ties red yarn around my wrists. This is our morning ritual. She puts salt in my shoes and sticks a saltshaker in my backpack as an extra precaution. Red keeps the Rusalki away. Salt melts ice, and the Rusalki are made from ice and anger.

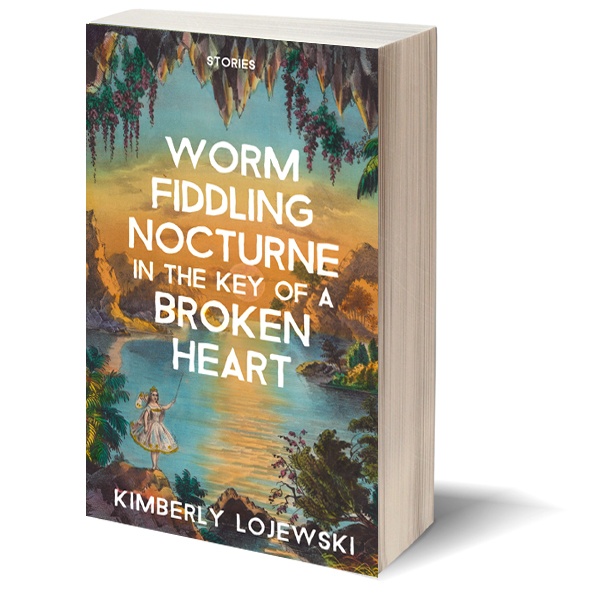

This story appears in Kimberly Lojewski’s debut story collection, published this year by Burrow Press.

This story appears in Kimberly Lojewski’s debut story collection, published this year by Burrow Press.

“Hannah!” she exclaims. “What on earth has gotten into you?”

I shrug. It’s the Rusalki telling me what to do, but if I tell her this she will say I’m being absurd, and tie red ribbons in my hair.

“Your parents would be turning in their graves to see you acting out like this,” she says.

But my parents have no graves. My mother is a Rusalka. Babci knows this. It’s why she takes extra care to make me not believe in them. It’s why the water witches want me. I begin to remind her of this but Babci stops me. Pop. Pop. Her knuckles crack, ending the conversation. Her arthritis is especially bad in cold weather. She can no longer remove her wedding ring, no matter how much butter or grease we apply. Instead she keeps it wrapped in white athletic tape and gauze, fearing rogue thieves will chop off her finger for the diamonds.

•

When new snow falls, the Rusalki sing songs to the frozen moon. It sounds something like stars and ice rubbing up against each other, terrible and beautiful all at once. When this happens, the villagers stuff cloth beneath the doors and pull heavy drapes across the windows.

Our village is made up of homespun Polish immigrants. The air is thick with the accents of the old-timers here. Their stories escape from brick chimneys, swirled with scotch, cabbage soup, and wood smoke.

Babci is one of them. Her voice is graveled with hardship. Despite her objection to my belief in the Rusalki, she’s as superstitious as they come. In our house, we always close the lids to the toilets. We throw herbs on the fire in the evenings so Babci can watch the swirls of smoke and try to make sense out of what they tell her. She times my showers (neither one of us take baths) and wipes all the drains in the house clean of any drops of water. In front of our house is a holly tree with crimson berries that protect us from the dead water witches. That’s what Babci believes.

The more Babci insists the Rusalki aren’t there, the more I feel drawn to them. They are terrible in the wintertime. They shriek and wail and their eyes glow silver and green in the moonlight. If my mother comes to my window, I wouldn’t know it. She wouldn’t resemble any picture Babci’s ever shown me. She’s been dead under the water for nearly sixteen years. These scaly creatures are her sisters. They come on her behalf, singing all night, and in the mornings silver fish and seaweed decorate the snow outside my bedroom window. Babci scoops them up with a shovel and burns them in a fire-pit outside.

Inside she surrounds us with clutter and color, and locks the windows shut every night. Our house is claustrophobic and full of junk. Silk flowers, tea sets, microscopes, baskets of Pysanky eggs, straw crosses, and knitted toilet paper cozies with dolls’ heads on them. Babci puts labels on the bottom of everything to designate who will receive her treasures when she dies. Though most of the stuff will go to me, there are several items that still have my mother’s name written on them. How do you pass your treasure along to a ghost, I want to know?

It’s impossible for Babci to admit the Rusalki are trying to steal me. Then she would have to acknowledge what happened to her own daughter. My mother disgraced Babci by getting pregnant out of wedlock. I don’t know who my father was, but Babci likes to say he was a soldier who died in a war. She says my mother drowned not long after I was born, that she was swimming in the lake and got tangled in weeds. It seems as unlikely to me as any Babci story. Babci says she sent my mother’s body back to Poland so she could rest in the place she came from, but I don’t believe her. I think she is still hidden somewhere under the water. Why else would the water witches come? Whatever happened to my mother’s body, her soul is still here.

•

We continue to play Scrabble when I return from school. I try to stop my swearing, but the urges are even stronger and, despite myself, I spell out Suka. Szmata. Kurwa. And then my mother’s name. Zofia. Until finally Babci swipes the tiles off the board and into the box. I feel terrible, but it’s as if someone else is controlling my hands. She tries teaching me pinochle, but her concentration is shot. The long nights are getting shorter. When winter ends, the lake in the forest will thaw and the Rusalki will become more powerful. In June they are at their strongest. All of the villagers stay away from the lake in June. June is when my mother died.

“I think we should send you away,” says Babci. I’m winning at pinochle, but that just shows how little she’s paying attention to the game. The wind howls outside and blows rain onto the window glass.

“I’m not leaving,” I say. “Where would I go? Besides, this is my home.”

“I don’t know,” she says. “But something has to be done.” Pop. Pop. Pop. Babci carefully unhinges her fingers and takes my hand in hers, which is swollen and hard. “Maybe we can send you away to another school,” she says.

I smile politely to try to ease her distress. We both know she doesn’t have any money.

She pulls her hands away and hops up from our game. She grabs a pail of salt from the kitchen and walks out into the rain, circling the house to coat my windowsill. Babci leaves the house less and less these days. It used to be that the other women in the village stopped by for a game of bridge or some chin wagging, but now this is rare. The villagers have noticed the trails of fish and lake weeds leading to our house. Nobody around here wants to draw the attention of the dead.

For dinner we have fried green peppers and processed cheese on slabs of buttered toast. I work on my Algebra homework, which Babci calls practicing my arithmetic. My concentration and furrowed brow seem to soothe her. She gets the brandy decanter out, along with a stationary set and an engraved pen. She writes furiously for a while and her sparrow eyes get shiny. I work at my arithmetic until she begins to doze. When she’s sleeping, Babci loses her fierceness and looks just like a grandmother. Any grandmother. Like the sort who has rose gardens and bakes cookies and isn’t battling dead spirits all the time. I peer over her shoulder and look down at the letter she’s writing. Dear Zofia. My eyes pick out a few sentences. I’m so sorry. I hurry across the words for fear that Babci might wake and catch me snooping. Please forgive me. Hannah is such a good girl.

I leave her there at her writing desk, putting an afghan over her shoulders, before going to bed. Whatever she’s sorry for, it’s probably best left between mother and daughter.

That night I wake to the water witches dancing in the old potato field beside our house. They’re doing a korowody, a Polish circle dance. Their bodies shimmer and glow in the starlight. Their voices sound like rippling water. Their hair streams about them in weedy banners. They are mostly naked, their skin tinged blue and green and so pale they are lit up like creatures from the deepest parts of the ocean. Some still wear the disintegrating scraps of the clothes they died in. I search for my mother among them. I don’t know how long I stand there watching, longing to hear the sweetness of their songs.

“Hannah!” Babci says sharply as I reach to unlock my window. She is there in my doorway in a long nightdress, her thick hair in curlers. “Come away from the window!”

“But look out there,” I say. “It’s not terrible at all.”

“There’s nothing there,” says Babci. “Come away from the window now, Hannah. And close the drapes. I won’t say it again.”

Babci sends me to the living room while she double-checks the doors and windows, the toilet seats and the faucets, then she lights the fireplace. She burns prayer candles and plays her old records loud enough to drown out any sounds from outside. I can still hear the singing, the occasional tapping, and some laughter, but I pretend not to notice because my grandmother is so obviously terrified. We sit together in the living room playing Scrabble and pinochle until the sun comes up, when she finally lets me sleep. She pulls the couch away from the wall and close to the uncomfortably warm fireplace. My sleep is sweaty and filled with Rusalki. I am dancing with them. My friends, my sisters, my mother.

•

When I wake up, the house looks different. Uncluttered. Things are missing all over. A statue of the Virgin Mary. Babci’s entire collection of beautiful, hand drawn Polish Pysanky eggs. Pictures of me have been taken from the wall. Wreaths of silk flowers. Teacups. Silver spoons. Vases. An embroidered pillow has disappeared from the couch while I was sleeping. And Babci herself is gone.

I run outside, still in my pajamas, and see that Babci has boarded up our windows. The ground around our house is covered in glittering scales that stick to my bare feet. Too many to pick up. Hundreds and hundreds of them, smaller than my pinky nail. There are wheelbarrow tracks in the scales and I follow them down to the lake.

This lake has always been here. From far away I can see the sun shining off its smooth surface. I have grown up less than a half-mile from its haunted waters, but I have only seen it a handful of times. Still, something is terribly out of place.

The wheelbarrow is tipped on its side at the edge of the shore and Babci’s treasures are strewn all around the lake like a child’s toys. The afghan I had tucked around her is draped across a fallen branch. Silver brushes and ivory combs float on the water, silk flower bouquets and stuffed animals bob along placidly, occasionally tangling in my grandmother’s silver hair. She is face down in the water, a red bathrobe on over her nightdress. Her ankles are wrapped in weeds. Tiny silver fish wrinkle the water around her, nibbling at her knuckles and swimming through her hair. Her cherished Pysanky eggs have been smashed into colorful confetti smeared across pages and pages of handwritten letters floating in the water.

I find a tree branch long enough to reach her and struggle against the debris and weeds to pull her to the shore. She’s been dead for a while. Her skin is ice cold and chewed away in places. I lay her out on her back and sit with her for a while, looking out at the objects floating on the water.

The sun is high now, and its rays dance on the lake. I am staring out at the debris when a flash of light catches my attention and I see Babci’s wedding ring sparkling on a lily pad. Beyond it, an unraveled length of bloody gauze leads down into the depths below. Zofia. It’s written on the scraps of cloth with permanent marker. Zofia. I nudge the body of a porcelain doll over with my foot. The name is scrawled beneath the petticoats. Zofia. An open music box floats past and I grab it and examine its underside. Zofia. Over and over again. I look closer at the dozens of yellowed letters lapping the shore, tear-stained, stuck to ice, sprinkled with eggshells. They all begin in the same way. Dear Zofia. I watch as the ink bleeds into the depths, where the Rusalki, silent now, wait somewhere below.

There is no more laughter, or screeching, or singing. The lake ice has stopped creaking. Everything is silent as fresh snowfall. Twin tears crystallize on my cheeks. Even the Rusalki are quiet now. I imagine them down there, content at last, slurping away at the leftovers of my grandmother’s soul.