At seventy-two, Johnny Ribkins shouldn’t have such problems: He’s got one week to come up with the money he stole from his mobster boss or it’s curtains for Johnny.

At seventy-two, Johnny Ribkins shouldn’t have such problems: He’s got one week to come up with the money he stole from his mobster boss or it’s curtains for Johnny.

What may or may not be useful to Johnny as he flees is that he comes from an African-American family that has been gifted with super powers that are rather sad, but superpowers nonetheless.

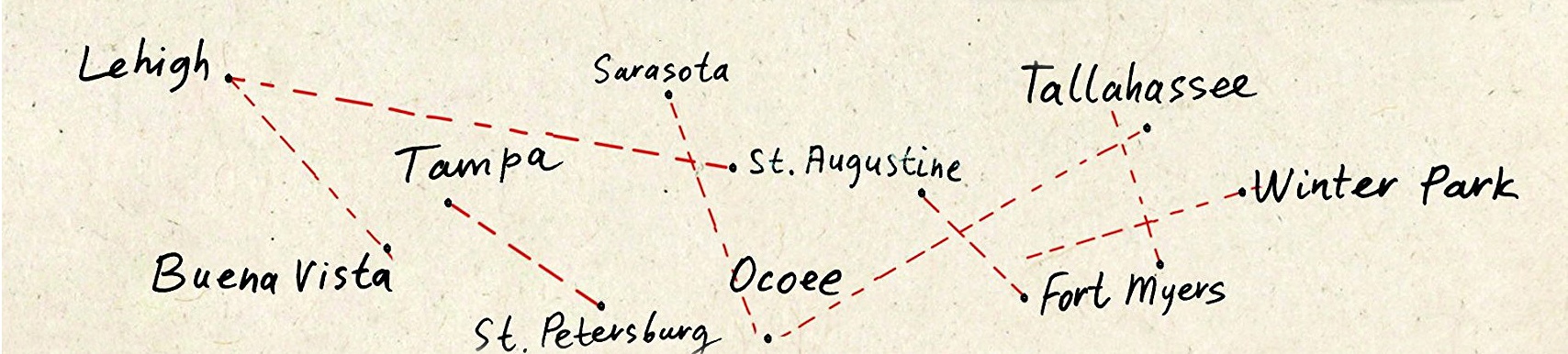

In the old days, the Ribkins family tried to apply their gifts to the civil rights effort, calling themselves the Justice Committee. But when their, eh, superpowers proved insufficient, the group fell apart. Fast forward a couple decades and Johnny’s on a race against the clock to dig up loot he’s stashed all over Florida.

Inspired by W. E. B. Du Bois’s famous essay “The Talented Tenth” and fuelled by Ladee Hubbard’s marvelously original imagination, The Talented Ribkins is a big-hearted debut novel about race, class, politics, and the unique gifts that, while they may cause some problems from time to time, bind a family together.

He only came back because Melvin said he would kill him if he didn’t pay off his debt by the end of the week. It was why he left St. Augustine, why he had no choice but to drive down to Lehigh Acres and dig up the box of money he’d buried in his brother’s yard fourteen years before. The only complication was his brother’s last woman, who was still living in the house, because of course he didn’t want her knowing what he was after. So he made something up.

“A toolbox,” Johnny Ribkins said, standing on the splintered porch of a wood frame two-story, while hard slats of Florida sunshine bore down on his back and the woman squinted from behind the screen door.

“A toolbox?” she said, gray grates masking her face like a veil. “Why you got a toolbox buried in the yard?”

“Oh, it’s always been there. Ever since we tore down the shed to build the basketball court.” He nodded toward a weed-covered rectangle of cracked cement at the far corner of the yard. “Just seemed like the safest place to put it at the time.”

A truck came barreling down the interstate on the other side of the fence, roar of exhaust merging with the mechanical drone of laughter coming from a TV playing inside the house. Johnny removed his hat, swatted at the moisture pooling across his brow, and stared at a rose tattoo that wound around the woman’s neck. He hadn’t seen her since his brother’s funeral but he had to admit she looked less crazy than he remembered. The lace top, miniskirt, and thigh-high boots were gone, replaced by a T-shirt, sweatpants, and white flip-flops. Her once-gaunt cheekbones were now fleshy and jowly, and her hair, deprived of the bright red wig she’d worn to the wake, was gray and cut short. He figured she must have been in her forties, about the same age his brother Franklin had been when he died.

Johnny smiled. “They old tools, see? Like for turning screws so old they don’t even make them anymore. Truth is I all but forgot about them until a couple weeks ago, when I got a delivery of antique watches at the shop.”

He pulled a handkerchief from the pocket of his shirt and scratched at a line of sweat tickling his left ear. It was hot out there and he could hear how lazy and exhausted his lies sounded. Luckily the woman was none too bright.

“They valuable?”

“Only if you a broken watch.”

A hearty “amen” and the sound of applause came from the TV inside the house.

“Tools aren’t valuable. The watches are, but only if they’re fixed. And really it’s more a matter of the fact that they don’t make them anymore. Now I’ve looked everywhere, even tried contacting the original manufacturer to see if I could get ahold of the designs to have copies made. And—”

Where was this going? Why was he wasting time trying to explain himself to some raggedy piece of interloping woman who didn’t even have sense enough to invite him inside and out of the heat, which would have been simple courtesy? He didn’t have time for this. He needed to find that money, get back to St. Augustine. And—

“So what, Johnny, you some kind of junkman now?” “Ain’t no fucking junkman.” It just popped out.

But when he looked up she was smiling. Her lip curled back to reveal the gold filling etched against her left incisor.

“I just thought because of the watches . . . You said they were old.” “They’re antiques.”

He reached for his wallet. His hands were shaking as he pulled back the screen door and handed her his business card: jonathan ribkins, acquisitions and repairs. ribkins antiques.

“Family business. Two generations . . . Didn’t Franklin ever mention it? He worked with me for almost twelve years.”

“No, we never discussed such things.”

She looked down at the card and then back at him. For a moment he thought he saw something crafty in her eyes, a form of coherency that hadn’t been there when he met her all those years ago, else he would have remembered it.

Then the TV let out another “amen” and he decided she must have found Jesus and gotten off the crack.

She handed him back the card. “You sure that’s all you want?”

“That’s all.”

She sighed. “All you Ribkins are so peculiar,” she said, then stopped because there wasn’t much more to say.

She shuffled down the dark hall. He waited until she was in the living room, then positioned himself at the center of the bottom step and started walking straight ahead, toward the interstate. And as he walked he couldn’t help but think about how sad it was to be digging through his brother’s yard again after all this time. His half brother, some twenty years his junior, whose existence he hadn’t even known about until he was a grown man, when their father got drunk at a party one night and confessed there was another son, someone named Franklin, living with his mama “out in the sticks,” and Johnny had been the one to go find him. He thought about all he’d been through since Franklin died, how hard he’d tried to put this place behind him only to find himself, at the age of seventy-two, right back where he’d started. This was especially troubling because Johnny made maps. That was his talent—not just what he did, but who he was, same way his brother had scaled walls. Johnny made maps and Franklin scaled walls, and for twelve years they’d made their living by selling the things they found on the other side of those walls, right there in the antique shop Johnny inherited from their father.

When he’d gone twenty paces he cocked his head to the left and started moving diagonally toward a large oak tree at the far corner of the yard. All of that was supposed to have ended the day his brother died. He’d made a promise to stop stealing, start living right, start doing right—to try to remember what it meant to be a decent man. And everything seemed to be going according to plan until one day he looked up and realized that somehow in his grief he’d wound up working for a man who was under the mistaken impression that he owned Johnny. So here he was, fourteen years later, crouched in the dirt trying to dig up enough money to appease a criminal.

He walked another ten paces, then stopped and stared down at a small patch of dirt and clover.

“You gonna fill it back up?” the woman called from the living room window. “I mean when you finished.”

“Of course.” Johnny smiled. He was still smiling as she disappeared back into the shadows of a house built for someone else.

He hoisted his shovel. He needed the money. That was all there was to it and there really wasn’t any point worrying about the how and why of it now. But it was also true that he’d buried that box for a reason and was breaking a vow he’d made to himself by digging it up. And that, in some ways, was just as troubling as Melvin’s threats. Because if all he’d tried to do since his brother left him hadn’t been leading anyplace but right back here, then what was the point? And if he couldn’t answer that question, couldn’t make sense of his own path or justify his existence even to himself, then what was he doing crouched in the dirt, humiliating himself just to hold on?

He put down his shovel and stared at an empty hole, aware that something didn’t feel right. He had a near photographic memory, but he had also stood on every inch of that yard, watched it from every conceivable angle, making it difficult to recall with any precision where exactly he’d stood when he first dug the hole he was looking for now. “Why you digging up that tree, old man?”

A heavy-set, big-eyed girl in a red T-shirt and blue jean leggings was watching him from the other side of the fence.

“What do you want?”

“I don’t want nothing.”

He reached into his pocket, grabbed a handful of coins, fished out the shiniest, and tossed it over the fence. The girl caught it with her left hand.

“Now go on home.”

“I am home,” the girl said.

She pushed through the gate, walked up the front steps, and passed through the screen door. Johnny shook his head and wondered yet again why his brother’s last woman had to be such a trifling mess.

“Of course she’s your brother’s child. Doesn’t she look just like him?” He was in the house now, standing in the dark hall while the woman stood in front of him with her arms folded in front of her chest.

The girl sat in the living room watching TV. “Why didn’t you say something?”

“Say what?” the woman said. “This is the first time I’ve seen you in fourteen years. How was I supposed to even find you? And anyhow, why? I don’t need anything from you, Johnny Ribkins.”

Johnny looked at the girl slumped on the couch with her feet up on a rickety coffee table, surrounded by huge piles of junk. The whole house was jammed with drab furniture dragged in from who knows where. But worse than the things he didn’t recognize were the things he did: the couch pushed against the far wall, his drafting table shoved in a corner underneath the TV set, the lamp with the crooked shade sitting on the floor near the window. Tokens of a distant past he’d all but forgotten yet somehow knew were out of order.

“You’re still living in my brother’s house.”

“This rattrap? In the middle of nowhere? I can’t even sell it.”

He felt something tense in his chest and glanced toward the yard. “Listen here, woman. You’ve got no right to be selling anything.”

“The name is Meredith, old man, and I already told you I can’t. But speaking of rights”—she turned to her daughter—“Honey? Why don’t you go on upstairs for a minute and start packing.”

“But I’m not going anywhere.”

“Get upstairs anyhow. Let me talk to your uncle.”

The girl sucked her teeth and stomped out of the room. “You heading somewhere?”

“Why?”

“I’m just asking.”

“Yeah?” She narrowed her eyes. “Look, man. You might as well go ahead and tell me what your intentions are. Because this is a common-law state. You know what that means?”

He did. He stared at the crooked lampshade.

“It means I got the same legal rights as a proper wife. Understand? Now I don’t want any trouble from you but I’ve been living out here for going on fourteen years now so I’ll tell you just like I told the bank. Whatever claim to this place you might think you have, you can just forget about. This is my house and —”

It was the heat, the heat of her presence, worse than the heat outside. He could feel his breathing catch in his throat and his blood pressure rise, even as he told himself to keep cool and remember why he was there. Melvin had given him just one week to come up with the $100,000 he needed to pay off his debt. And a part of him knew that the only reason he’d been given even that much time was because Melvin didn’t believe Johnny could do it, was just waiting for him to fail. But that was because Melvin didn’t know about the hole Johnny had dug. Which was to say, how selfish he’d been before his brother died.

“I just want my tools,” Johnny cried, then stopped because he could feel himself about to give away how badly he wanted them. He reached for the handkerchief in his pants pocket, put his head down, and patted his brow, trying to channel the appearance of a harmless old man who was confused or anyhow peculiar enough to have come all that way to fetch some worthless junk. And all at once it occurred to him that maybe he was just a harmless, peculiar old man—hunched over, blinking back confusion and grief as he stood in the dark hall of a house he’d helped his brother build, yet had given up any claim to long ago.

“Johnny Ribkins, you may not stay here indefinitely, digging up holes in my yard.”

“Yes, I understand. I just . . . need a little more time. I got distracted by the girl and it’s hot out there.”

Meredith opened the door and made a sweeping gesture with her hand.

“Her name is Eloise, by the way. In case you were curious.” She shut the door.

Johnny put his hat back on. He stood on the porch for a moment, trying to absorb the quiet of the world outside. Then he took a deep breath, eased himself onto the top step, and stared at his empty hole.

Strange and pitiful, that was what his life had become. His current circumstance was undignified but, if he was honest with himself, no more so than the circumstance that had preceded it: selling his maps to Melvin Marks. That was the part that should have never got started. But decent man or no, he still had to make a living; after Franklin left he couldn’t bring himself to go back to working alone, so he’d started working for someone else. Sitting in a small room, drawing up blueprints, waiting for his share. Of course he was getting ripped off. But when he tried to get out of it, Melvin wouldn’t just let him leave.

You’re not going anywhere, Johnny Ribkins, so you might as well sit your ass back down. You signed a contract when you came to work for me and I can tell you exactly how much it would cost to buy yourself out, because, you see, I got it all written down.

So after a while Johnny started giving himself little wage adjustments. Whenever an unexpected expense came up, it wasn’t hard to find ways to simply take what he needed; this he did not consider stealing because in truth it was always far less than what he was owed. It was just a fact that Melvin was getting rich off Johnny’s maps, so rich that for a long time he didn’t even notice how much Johnny was skimming off the top. It seemed to keep everybody satisfied and for a while everybody was happy—right up until the day Johnny got caught.

The door swung open and Eloise shouted, “It’s like one hundred degrees out there. I’m thirteen and I don’t like shrimp,” then sprinted past him down the steps. She ran over to the other side of the yard and started playing by herself, throwing rocks into the air, then spinning around and catching them in alternating hands, all the while weaving in and out of the sunlight flashing through the branches of the oak tree.

Pull yourself together, Johnny thought. There was nothing to be done about his current situation except be a man about it. He needed to focus, remember where he’d buried that money, and then get back to St. Augustine and deal with Melvin as quickly as possible. That was the way the Ribkins brothers worked: in and out, no flinching, no fucking around. Johnny drew up blueprints not just for the walls he could see but also for the walls behind those walls, and his brother hiked his pants and scaled them. Later on, Franklin would tell Johnny how he’d been exactly right, how he’d turned a corner or pushed through a door and the passageways in Johnny’s pictures seemed to magically appear. “How do you do that?” Franklin sometimes said. Just like sometimes Johnny asked Franklin how he managed to get up there, get up and over that wall or fence or window ledge and then come back to show Johnny whatever it was he’d found on the other side. The truth was Johnny had been drawing up blueprints of buildings he had no access to since before he could read, and Franklin had scaled walls the way other boys masturbated, for years never managing to accomplish much with this miraculous skill beyond a series of trespassing and petty theft charges. No reason for it, just something they’d always been able to do that never made much sense and only rarely seemed useful. Until one day they found each other, and for a while, everything seemed to click.

“Are you really my daddy’s brother?”

The girl was watching him from the shade of the oak tree. “So I’m told.”

“Can you prove it?”

“Who else would I be?”

“That’s what I’m trying to figure out. You got some kind of identification? Let me see your driver’s license.”

He reached into his wallet and handed her a business card. “Satisfied?”

“Mama said you wouldn’t have come around unless you wanted something. She said Ribkins are real good at looking after their own but they don’t care a thing about anyone else. That’s why she doesn’t want you in the house. She’s worried you might get confused, start thinking you might as well stay.”

“Yes, I caught that.” “Is it true?”

“No. Where are you all heading off to?”

“Oh, I’m not going anywhere. She got a job working on a riverboat for the shrimp festival out in Clearwater. She does it every year but I already told her I’m not going this time. I’m staying right here. I’m thirteen now—I can take care of myself.”

“Okay,” Johnny said.

He heard a whistling sound and turned his head. A group of children had gathered by the gate and were calling Eloise toward them.

“You know, you don’t look a thing like my daddy’s picture. Plus you’re old. If you two were brothers, how come you’re so old?”

“That’s something you’d have to take up with another party, now, isn’t it? Seeing as how I didn’t have much to do with it.” He smiled. “We were brothers all right. Half brothers. On the Ribkins side. Trust me, we had enough in common, in the ways that count.”

She handed the card back. “Naw, you keep it.”

She slipped it in her pocket, then turned around and ran across the yard.

Johnny knew the girl was just telling the truth: he was old. Old and tired. For all he knew, it was a sign of this very infirmity that he seemed to keep forgetting how old and tired he actually was.

He looked back at his hole.

He stood up, positioned himself on the bottom step, and started walking again, this time channeling the cocky stride of his much younger self. He narrowed his eyes, pursed his lips, and tilted his shoulders so that his left side rolled back below his right. He dropped his hips and let his legs slide out in front of him, then sidled across the yard in this manner for a full twenty paces. When he stopped, he realized he was almost twice the distance farther than his careful, plodding steps had taken him earlier. He cocked his head to the left and took ten more winding steps toward the oak tree. He hoisted his shovel and started digging.

Yes, sir, he thought. How you think you got this old? Been around for years, and trust, this ain’t nothing. If there’s one thing you do know it’s how to survive this world. Johnny Ribkins always lands on his feet.

He lowered his shovel and felt the sudden crack of metal against metal. He got down on his knees and pulled out a rusted box.

“Thank you,” he said out loud. He glanced over his shoulder. Eloise was standing on the other side of the fence, leaning against a telephone pole that rose up at the edge of the highway while a boy crouched down in front of her, reached inside a book bag, and pulled out two large cans of cut corn. She shut her eyes and made an “okay” signal with two fingers of her left hand. The boy stood up, leaned back, and hurled the cans as hard as he could straight toward Eloise’s head.

“No!” Johnny gasped. By the time he understood what was happening Eloise was holding the first can in front of her face. Her eyes popped open as her left hand floated up just in time to catch the second.

“It’s all right, Mister. She caught it, see? She always catches it.” The boy smiled. “We just playing.”

Johnny turned back toward the house.

______

From The Talented Ribkins. Used with permission of Melville House. Copyright © 2017 by Ladee Hubbard.