This September Burrow is proud to release Pat Rushin’s third book, Quantum Physics & My Dog Bob, a short story collection.

This September Burrow is proud to release Pat Rushin’s third book, Quantum Physics & My Dog Bob, a short story collection.

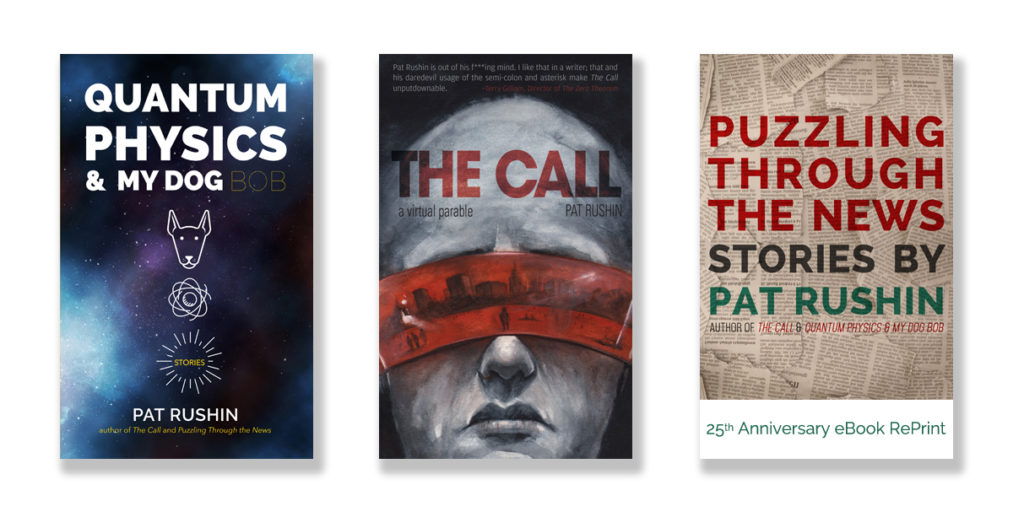

Pre-orderers (as well as 2017 Burrow subscribers) will get the book extra early. On top of that, we’re offering a pre-order bundle that includes Rushin’s previous novel, The Call, and his debut story collection, Puzzling Through the News, which is back in print with our 25th anniversary ebook edition. Three books for a mere $25.

In anticipation of the new release, Rushin sat down with Rebecca Fortes to discuss his new book, how to read a story collection, and how little he knows about physics.

______

How do you, personally, read story collections: do you read each story in order, or skip around? Does being a short-story writer publishing your second collection change your approach?

Normally I read a short story collection front to back, the way the author and editor intended, I assume. I figure somebody went to the trouble to arrange this material for me, so I may as well cooperate.

On the other hand, as a former editor of The Florida Review, I know how I arranged the appearance and order of a number of disparate stories, poems, and essays by a number of disparate writers. You’re always looking for that kind of unstated flow between different works, how one writer’s story might somehow comment on the story it follows in the rotation. So, again, you’re assuming a front-to-back read… But I know people don’t really read like that. Some people start at the end—thumbing the pages left-handed, as it were.

So here’s the basic trick. You front-load and back-end your strongest stories. This covers both sinister and dexterous readers. Then you cover your middle ground by putting the absolute best story right smack dab in the middle of the book, for those like myself who are bi-dexterous.

But of course all these tactics remain moot so long as you never include a weak story in the collection, which I assure you we (my editor and I) cut a couple of out of the Table of Contents early on.

The stories in Quantum Physics are populated by “everyman” characters, and you’ve said that Roberts, the protagonist of your previous book, was also intended to be an “everyman.” What is it about this archetype that appeals to you?

I’m a sucker for the everyman character, the average Jo who knows no more than you and I, who has to struggle along the best he or she can figuring out which way to go. Kafka’s everyman in “The Hunger Artist” inspired my “man” and his impossible vow in “Vow.” But I think the “everydog” archetype has more of an appeal for me in this book. Every dog has its day, right? And the Bob of the title story is an everydog, though he’s based on my longtime friend Poco, RIP. Named or nameless, many of my characters just tend to represent the way I see the human race, which to my eye includes dogs.

Some of the stories in this collection have very specific settings: “Way” and “Spider Rock” both take place on the Navajo Reservation. Stories that err closer to the strange, however, could take place anywhere, almost like an “everysetting,” if you will. What role does setting play when you’re putting together a story? How much are you thinking about it when you sit down to write?

So in this collection, I have three stories with very specific settings—“Spider Rock” (AZ), “The Garden” (North FL coast), and “Touched” (NYC)—and each of those stories depends on its setting being a major ingredient in the story.

Then I have three more stories set in an unspecified Florida location—“Quantum Physics & My Dog Bob,” “Every Goddamn Thing,” and “Dig”—and each of those needs it just for the heat, if nothing else. Plus I live in Florida, so it’s the natural default location when I start a story unless there’s a reason to change.

Finally, I have three stories—“Vow,” “Call,” and “This Is Just to, Like, Clue You” with what I consider generic settings of “everysettings.”

Places really, really, really have to have an effect on me for me to use them in my fiction. The place I live right now is lovely but generic, so I don’t really picture it when I’m writing. But I’ve lived and worked in places that just won’t let me go, and I’ve set stories in Cleveland (hometown), Baltimore (adopted hometown), D.C. (everybody’s adopted hometown where you don’t even have to pay to enter a museum), New York (my wife’s hometown), and places I’ve visited—Maine, Arizona, Napa Valley, New Orleans, Asheville… the list can go on, but it helps if I’ve spent some time in the place so it’s like a second skin to me.

Do you have a favorite short story writer, or a short story writer whose influence you felt strongly in writing this collection?

So many over so many years. I already mentioned Franz Kafka, and that’s a big one. Let me add Italo Calvino’s story collection Cosmicomics, my mentor John Barth’s Lost in the Funhouse, my other mentor Stephen Dixon (just every damn story of the hundreds and hundreds he’s published), and finally Grace Paley, Grace Paley, Grace Paley. Amazing Grace!

Werner Heisenberg, the scientist credited with conceptualizing the uncertainty principle, says, “The atoms or elementary particles themselves are not real; they form a world of potentialities or possibilities rather than one of things or facts.” This, to me, sounds a lot like writing fiction: forming a world of potential or possibilities. Given the title of this collection, can you talk about the influence of physics in your writing, and in this collection particularly?

Here’s the poop on physics and me.

I grew up wanting to be a “scientist.” I read all kinds of science fiction. I subscribed to science magazines. I was looking into where I could go to college to study oceanography. This was all grammar school stuff. Once I hit high school and hormones and smart-assed-ness kicked in, I got kicked out of physics class—and chemistry and biology and even math—for being the wise guy cracking jokes from the back of the room at every opportunity. Turns out I really didn’t have a talent for science, but I had a talent for not knowing when to keep my mouth shut.

So now science is simply magic to me, because there is literally nothing up my scientific sleeve.

Talk a bit about how you dabbled in sci-fi before getting your formal creative writing degree. How was your sci-fi (and sci-fi in general) received in those writing programs at the time? And how does this all play into writing “Touched”?

I did more than dabble. I devoted myself to writing science fiction all through my undergrad years and through my first M.A. degree in English at Ohio State. My very first publication would have been a science fiction novella called After the Dreams Began if Starwinds, the magazine that accepted it, had stayed in business another year or so… but alas.

Now at that time OSU didn’t have a formal creative writing program, and I never took a creative writing course there, but they had just started the option of allowing creative rather than scholarly works to fulfill the thesis requirement. All I had to do was get me a thesis advisor. So I pulled out my best science fiction stories, submitted them to a professor named Bob Canzoneri, and waited for him to be dutifully impressed with my talent. Bob agreed with me that I could write, but after patiently reading a 100 or so pages of my sf, he penned me a brief response: “Pat, why don’t you try writing something real?”

That advice truly pissed me off, but I’d be damned if I could stand to write one more lit-crit paper, let alone a full-scale scholarly thesis, so I gave “mainstream lit” a shot, got my “real” thesis accepted, and used that a couple of years later to get me into The Johns Hopkins Writing Seminars, where I continued to write reality-based stories often inspired by some seemingly scientific nugget or other that probably made no scientific sense.

My first publication ended up being a story called “Speed of Light,” in which my protagonist is informed by his wife of thirty years that she wants a divorce, and the next day the speed of light inexplicably starts speeding up all over the universe.

“Touched” marks a return to my earlier days in many ways, but it’s more speculative fiction than science fiction. After all, I got a “C” in high school physics!

In your view, what binds the stories in this collection?

The fact that I actually wrote every damn one of them and they are all exceedingly well-written. Next question.