Be an honest writer. Honest writing is heart-wrenching.

Today, in a number of genres, fiction writers use their platform to advocate for ideas they deeply believe in. Nicole Saunders is no different. As a lawyer and writer of Jodi-Picoultesque novels, she uses her platform to fight for women’s rights, examine class differences, and push to open up the conversation on disability rights and pride in this country.

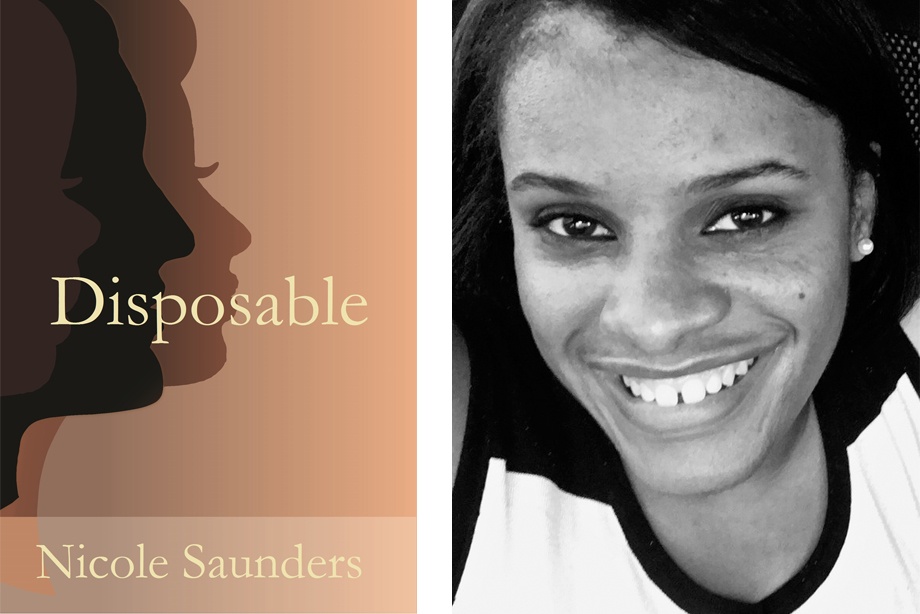

In Saunders’ novel, Disposable, a broke college student agrees to become a pregnancy surrogate for a wealthy family. All goes well, until a fetal abnormality appears on a routine exam. In the aftermath of the test results, the reader learns who is truly disposable and who should be valued.

•

Jessica Hatch (JH): Let’s start by discussing the cross-section between your career as a lawyer and your writing career. Legal writing and creative writing are different disciplines. Is it difficult for you to juggle your work life and your writing life? Alternatively, how do the right- and left-brained tasks feed off of one another?

Nicole Saunders (NS): I first noticed the difference between legal writing and creative writing in law school at the University of Florida. Legal writing is succinct yet thorough. Ambiguity is a no-no.

Creative writing is different: embellishment and elaboration are crucial to paint a detailed portrait for the reader. At first, I struggled to turn off my creative writing brain when doing my legal work. I’d write extensive and colorful essays when my professors wanted clear, clean, straightforward work. My law school professors would praise me for being a gifted writer, and then give me a B in the class. It took me a while to understand: creative writing came to me naturally; legal writing required more work. Ultimately, I decided to embrace the differences. The more I did that, the easier it became.

I believe right- and left-brained tasks feed off of each other well. Legal writing and creative writing are two sides of the same coin. Legal writing takes an event or series of events and reduces them to clear, understandable principles. It is like taking a detailed picture, extracting the key components, and explaining it in its simplest terms. Creative writing is the opposite. Creative writing takes an emotion or a word and builds upon it to craft a picture. Legal writing tells you what the judge said in a case. Creative writing describes how the courtroom felt and how the judge looked as she was making her pronouncement.

JH: I love that illustration, and I suppose it finally shows that courtroom dramas lie on the side of creative writing! According to your website, your mission statement as a writer is to “advocate and entertain.” Can you explain what this means to you? How does this ethos come through in your work?

NS: To advocate and entertain is to utilize artistic expression to further an idea. The arts are crucial to advocacy. Whether it’s television, theater, movies, or books, entertainment has the power to advocate for its creator’s ideas and influence its audience. Writing fiction can provide the author with a unique opportunity to push for ideas that may be unique or even progressive, under the surface, through characters and plot, without explicitly coming out and sharing the idea.

For example, while Disposable is a legal drama on its face, it’s also an advocacy piece for life, disability rights, and women’s rights. Those concepts come through in both the ideas and characters in Disposable, but Disposable is also a fun book. It’s exciting. It’s entertaining. So, through the book, I advocate for ideas that matter to me, I try to challenge the reader, but I also take the reader on a wild ride.

JH:Do you look up to lawyer-writers like John Grisham, or do you find them too commercial?

NS: I admire John Grisham’s success and I especially loved his early works, but I couldn’t write that much about the law! While legal concepts will always be part of my books, I envision them taking more and more of a backseat as I develop as an author. I strive to be a writer who uses the context of law to tell stories.

JH: What conversations do you hope your book inspires in readers?

NS: Disposable makes strong assertions about what we as a society value. I hope it sparks conversations about the current direction in which we’re moving. I would love to be a fly on the wall when conversations like that take place.

JH: I find myself coming back to your title time and again. Disposable is such a poignant word, especially for a book that deals with class differences. Which characters do you feel are disposable? For instance, in a world where the Caslons can hire anyone to carry their baby, does Annalyn feel disposable? Is there a point at which she is no longer disposable to, say, Abington?

NS: Yes! It makes me so happy that you see that concept in the book. The main characters who are disposable from society’s standpoint are Gerline (Abington’s wife), Annalyn (their surrogate), Akon (their lawyer), and Gabriel (the child born through surrogacy). However, they’re disposable for different reasons: Gerline, because of her difficulty bearing children; Annalyn, because of her difficult background and financial instability; Akon, because of his disability; and, Gabriel because of gestational age and disability. By framing the novel within their points of view, I subvert this quality society puts on them, of being disposable. Without them and without seeing the world through their eyes, the novel as it stands would not exist.

JH: Great point. I have to say, I love the way that you bring in a third point of view, with his own biases and strengths, through the Caslons’ lawyer, Akon Tahiri. At first, it seems that this lawyer with a disability doesn’t have much in common with his clients, but when he learns that the fetus has a physical abnormality—making it unwanted in Abington’s eyes—he must be wondering if the Caslons think of him as disposable due to his own physical difference. Did you originally have three storylines to braid together, or did the lawyer come into being during revision?

NS: Akon has always been a part of the story. He’s the character to whom I feel closest. When I first began writing Akon, though, I wasn’t sure the direction I wanted to take the character. The more I wrote, the more he took shape.

JH: Akon is wheelchair-dependent and has a bit of a drinking problem, which affects his personal and professional life in scenes like his son’s basketball game. Was it important for you as an advocate to create a character that was not the “disabled saint” stereotype we often see in books and movies?

NS: Definitely! I have used a wheelchair all of my life. I’ve known other people who have used wheelchairs or had other disabilities. None of us are perfect. Just like everyone else, we have vices. We drink. We yell. We fight. We love. We have dimension. So, yes, it was very important to me to show Akon not as a caricature, but as a real man with real strengths and real problems.

JH: As you’ve said, this book takes on some pretty big issues, like disability rights and women’s rights in the frame of gestational surrogacy. Are there any ways that you fear this book will be misinterpreted by readers? For instance, if you were pro-choice, would you fear that it may be seen as pro-life across the board, instead of in this one particular case where the child would be carried to term if it weren’t for a test result?

NS: I did worry about misinterpretation at first. Personally, I am pro-life, but this is not a pro-life book. This is a book about life and people and experiences. There certainly are pro-life themes. People have said that. I’m happy people see those themes, but many people who have read and enjoyed the book are pro-choice. As some of the book’s reviews have shown, people interpret the book in many ways. That’s the point. It is up for interpretation. To me, the only way to misinterpret the book is for a reader to decipher that the book is about praising society’s stereotypes. That would definitely miss the point.

JH: Definitely. As someone who has now spent a couple of years in the Florida writing scene, how do you feel about it? This is the state of writers of color like Zora Neale Hurston; do you feel that we’re embracing diverse writers now? If you feel up to sharing, what can writers and readers do to support #OwnVoices in Florida?

NS: Yes, I am so honored to come from a state with such a rich literary history. But writing is hard! When I first started writing, I knew nothing about publishing or editing. I learned on the job, so to speak.

Fortunately, I believe space is opening up for diverse writers telling diverse stories. Social media has played a large role in creating that space. Social media platforms, like Untamed Publishing, have created spaces for diverse writers, especially women of color, to create and connect.

To me, supporting #OwnVoices is as simple as living in your truth. Be an honest writer. Honest writing is heart-wrenching. It requires the author to delve into the recesses of her imagination to extract truth and then share it. For example, I did not want to create a glamourized version of a wheelchair-user in Akon. I drew upon my own experience to do that. I told my truth (albeit slightly enhanced) through Akon. I encourage other writers to do the same.

And, for the reader, support is all about reading, rating, and reviewing. Exposure is crucial to supporting authors.

• • •

Nicole Saunders is a prosecutor and fiction writer living in Jacksonville, Florida. As a novelist, her mission is to advocate for populations often left voiceless. In addition to DISPOSABLE, Saunders is hard at work on a second novel. Say hello on GoodReads, at www.disposable-thebook.com, or on Twitter and Instagram at @Nickifxnwriter.

If Burrow Press’ readers are interested in Nicole’s novel, they can download the ebook version for free right now on Kindle Unlimited. I understand if BP’s editorial guidelines mean this is a no-go, but all the same, if this information could be added to her byline or to the end of the article, I would greatly appreciate it, and I know Nicole would, too.