The author has provided an accompanying Spotify playlist for this essay. Listen here.

At The Castle in Ybor City, Thursday nights slipped into Friday mornings like easy exhales. It’s not where I imagined I’d be spending my late twenties, but I couldn’t stay away. Nearly thirty years after its construction in 1992, The Castle is still notorious for its counterculture scene: Fridays are billed as Midnight Mass (“gothic and industrial”), Saturdays are called Carpe Noctem (“dark electronic”), and posters in the bathrooms advertise cosplay and sexdoll events. The building’s exterior looks like a cartoon fortress, turret and all. At least one person has allegedly asked for their ashes to be scattered on its premises. On Thursdays they played indie pop.

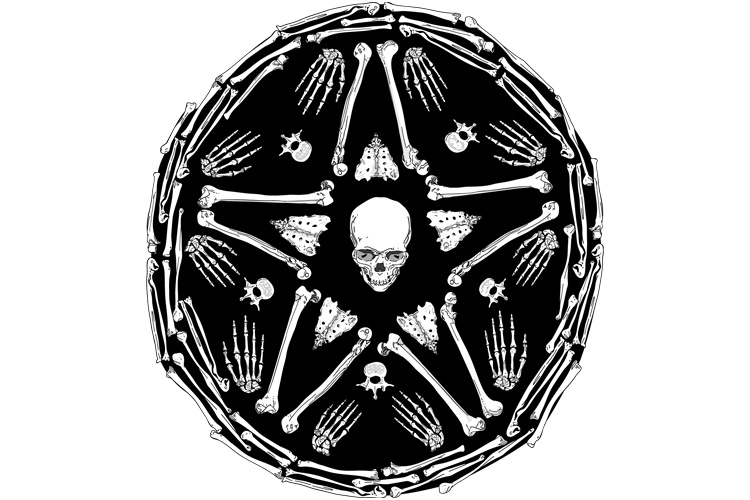

Entering The Castle was akin to a goth middle schooler’s choose-your-own-adventure fantasy: You walk through a wooden door that is rounded at the top and covered in ironwork reminiscent of a generic medieval time period. Once inside, you are eye-level with posters of naked men as an actual one checks your ID, stamps your hand, and affixes a wristband that indicates whether or not you can legally drink alcohol. Overhead, red lights glint off a plastic chandelier. It’s decision time. Ahead of you are wide, carpeted stairs leading up to the second floor; to the left is the dungeon where a pentagram of bones hangs above the DJ stand; to the right is a stone-topped bar. Each space has its own set of music playing, and beneath the chandelier the sounds blur together so only the bass’ thrum is distinguishable. Which way do you go?

There was an element of ritual to my Thursdays, and after so much repetition the nights have blurred together like a movie: idealized and forever in the present tense. As 10:00pm rolls around, we—Mark, Felicity, Arizona, and I—slowly begin to congregate at Arizona’s apartment. She is the linchpin of our group, and her living room is well lit, with high ceilings and framed Modest Mouse posters and a Pantone palette calendar in shades of blue. We finish getting dressed: eyeliner, kitten stockings, dog collars. My friends pull down hard cider and vegetarian Jell-O shots that aren’t set. I gulp Red Bulls and chain-smoke. The mood is expansive. I drive.

Mark shouts from the backseat during the thirty-minute trip downtown. Once we arrive at The Castle, the night’s film splits into one of two scenarios. The first: Mark sings along with the hair band hits, Love shack, bay-beeeeee. He drags his hands from his face to his waistband, he pushes his hands through his floppy bangs, he clenches his hands into fists and pulls them toward his body, Why don’t we give ourselves one more chance? The more he drinks, the more his movements loosen. While Arizona, Felicity, and I remain clustered on the dance floor, refusing eye contact with all men, Mark flops onto the empty stage beneath a large flatscreen playing music videos. He then gets up and makes laps around the top story of the club—passing the St. Andrew’s cross and the Gothic windows, weaving around the go-go dancers on raised plexiglass platforms who move as if through water, lit from beneath in a blinking redblueredblueredblue—propelled by that inexplicable drunken inertia. We ask if he is okay, and Mark insists he is fine, he is fine, he is fine, before sitting down in a corner and falling asleep. This is our cue to leave, gathering up Mark and placing him in my car’s passenger seat.

The second scenario: Mark doesn’t pace around the club, but instead remains in our circle on the dance floor, and we stay until the lights come up. Though Thursdays are advertised as Indie Night, the playlist is based on contemporary requests with some nods to the late 70s and 80s: think Iggy Azalea to Iggy Pop. Arizona twirls to her favorite songs, So, yeah, we’re werewolves, stepping gracefully in white platform shoes. When the floor suddenly clears in a herd movement toward the bar, she shimmies across the open space, elbows swinging, taking up as much room as she can, laughing, Why you looking at me now? She swings her long hair.

Felicity is immaculate, the easiest of us to love. She radiates patience. At the bar, she smiles politely to men who insist that they are interesting; on the dance floor, she raises her eyebrows in perfect, non-judgmental surprise at the music’s sudden genre shifts. She is also the only one of us who can actually execute a dance move. Her favorite songs are pop hits, Nobody pray for me, the ones playing on the radio that I’ve never heard before. “I don’t know this,” I shout again and again. She tells me the artists and song titles, gracious. She dips, It can only mean one thing, bends, smiles contentedly at her own movements like a cat curled in a patch of warm laundry. I am lucky to have friends who will keep dancing when the lights go up halfway through the night’s last song, even though we can see one another.

•

One of the smartest men I know is a cartoonist and a former member of a Nü Metal band. He once told me that the music we listen to in our adolescence remains a master key that forever unlocks the emotional frequencies of that decade. I replied, “Uh-oh,” and avoided eye contact.

As a teenager, I liked music with a fast tempo—the kind that is best listened to loud. Nuance of sound has never been my forte. My first concert was Slayer, one of the most well-known thrash metal bands. They’ve been around since the early 80s and in many ways exemplify the genre’s stereotypes. It’s possible to buy stickers and placards mimicking the hand-washing dictums in public restrooms that read, Employees Must Carve Slayer Into Forearms Before Returning to Work. A pentagram replaces the usual image of lathered hands. Imagine me at sixteen, dressed for the show: dark pants with ragged cuffs, dog collar, rings upon cheap rings, leather cords around my neck with brass alchemy symbols. At the show, meaty men in their forties wearing black cutoff t-shirts politely kept me from falling beneath the press of the crowd when “Raining Blood” began. When I ran into the mosh pit, my friend’s swinging fist glanced off my cheekbone, and the next day at school, I ran at him, jumped, and held on. A few years later, Jeff Hammond, the guitarist, contracted a case of flesh-eating bacteria. Slayer’s shows have always been like this; a 1998 review in The New York Times describes the concert experience as “no more or less interesting than watching an enormous furnace for 90 minutes.” The “pleasure” of it, the review reads, is “purely physical.” That last sentence is obvious though. Humans have always known that catharsis comes when bodies move through space.

A few years later, I saw Tool play in a massive sports arena in Richmond. Like Slayer, the band has been criticized for their disturbing lyrics, though this hasn’t stopped them from also winning Grammys. Tool’s music is trippy. The titular song from their album Lateralus takes its time signatures and lyrics from the Fibonacci sequence. A ten-minute music video for their song “Parabol/Parabola” features stop-motion animation and imagery drawn from Kundalini yoga. I watched it with friends after eating two gel tabs and wandering through the woods, and someone said, maybe out loud or maybe not, It’s like they’re showing what’s in my head.

At the time of the Tool concert, I was living in a near-stranger’s house in a small town on the water. A cop pulled us over on our way to the show. The van we rode in was oversized and white, more suitable for construction equipment than passengers. Most days, blue vodka bottles rolled around beneath the seats every time the brakes engaged. The cop asked, nicely, to search the vehicle and didn’t look too hard. Since he didn’t find anything, I barely remember the concert. We were to the left of the stage, up in the seats. There was blue lights, smoke, drums, Maynard. That night, I almost went home with another stranger.

That night, I fired a gun into the night of the highway for fun. The first single off Tool’s Undertow album is titled “Sober.” Maynard mumbles in the outro, I want what I want, I want what I want. I worry that if The Cartoonist is right this means I will always feel needlessly pitted against the world.

•

So much of life and art is a matter of perspective

and focus; to create a happy ending is often

to look away at the right moment.

I’d first heard of The Castle a decade before becoming a Thursday-night regular. The place had mythos. An exes’ friend, who worked as a dominatrix, spent weekends there with her clients. Later, my college friends would tell me convoluted stories of their late nights there. I’d listen and sigh and then, as soon as classes ended, head in the opposite direction of Ybor, driving home over a ten-mile bridge. The Castle pulled at my imagination, but I stayed away. As embarrassing and dramatic as it sounds now: I was afraid.

The aesthetics of my adolescence had swung violently between having too many feelings and wanting to have absolutely none, and the inevitable fallout resulted in an over-commitment to responsibility. I quit doing the fun drugs and started taking the right ones. I moved down the Eastern Seaboard. I went back to school full-time the semester before my twenty-first birthday. I arranged my new life in such a way that no conditions could lead to relapse—of either substance or mood. No more powder, no more late nights, no more psych wards. This was, I thought, the task of becoming a real girl, of growing up and getting well: working and working and working until my restless energy was spent, not having too much fun lest it tip into another dangerous upward spiral.

•

My adolescent CD collection was full of Tipper Gore’s Parental Advisory stickers. I also kicked holes in my bedroom walls. In some ways, it was all very predictable. I bought myself a ticket to see Slipknot and traveled sixty miles to the concert. This was after Paul Gray, their founding bassist, had died of an accidental overdose, after they’d stopped setting one another on fire during their performances. Slipknot became popular in the late 90s, and they’re still performing and making music twenty years later. It’s still a big production. Contrary to the myths of my high school years, their masks are not taken from the Nightmare Before Christmas, and I suppose one good thing about being in a masked band is that aging is much less apparent. I only recognized half the songs, but I knew all the words to the familiar ones. I’d heard rumors about their drummer playing on a rotating platform that would eventually spin him upside-down, but they proved unfounded. At the end of the night, I caught one of the guitar picks thrown into the audience. I had turquoise hair at the time, and it was pouring rain when I left the auditorium. I rode home drenched and screaming with adrenaline. The next morning, the back of my neck looked bruised from where it’d taken on the color of my hair, but I went to work regardless.

Another time, I spent a few hours lying on the ground, baking in the May Atlanta heat, listening to the Deftones. This was at a day-long festival, and I was too tired to stand close to the stage or run through the mosh pit, but also unwilling to go home. I had reached the point of simultaneous thirst and needing to pee, yet it was worth it. I imagined the cover of their self-titled album: roses and a skull. Only the drums’ vibrations in the earth kept me from feeling like I was floating away.

I’d said before I liked loud, fast music as a teenager, as if it’s something I outgrew. This is misleading. I still routinely frighten unsuspecting passengers with the sound of booming double-time drums when I start my car’s engine. I jump up and down until it feels like my neck is going to let my head fly right off my body. It’s been a decade since I’ve hit a wall.

•

Flash forward to my weekly Thursday nights. The transition from fearful asceticism to racing the sun to sleep was boring: gradual, involved lots of therapy, and happened without my noticing. It seemed like one night I was afraid of what it would mean to see 3:00am too many times in a row, and then the next I was standing in my kitchen after dinner making coffee and grabbing a Red Bull out of the fridge.

How many times can we put on a costume until it is no longer a costume? On our way home from dancing, I think my friends and I are all a little in love. They have seen a sliver of the person I used to be, even if it is couched in dress-up and play-pretend. I feel exhausted and unburdened. I have been struck neither drunk nor manic. Nothing triggered, nothing spiraled; my fears unfounded. It feels like some kind of magic. Of course, I have not yet ascended beyond my resentments, and my taste in music hasn’t much improved. But I am lucky to have survived growing up. The girl I once was and the woman I am now can both agree on this: Thankfully, there are no mirrors on the dance floor.

I drip sweat, my clothes heavy. When I hand Arizona a bunched up ten-dollar bill from my pocket for drinks, it is damp. I complain about my knees hurting, that I am too old for this, and then the next moment I am all hips. I alternate between Red Bull and water, and it’s sometimes hard to tell what is the overenthusiastic bass and what is my heartbeat. The truth is I am always looking to forget myself. Even still.

It seems that no one on the dance floor thinks about anything—everyone is loose and spilling, swept up in currents of vodka and gin. I miss the feeling of not feeling. But on those same nights, when I sit by myself on the sidelines and smoke cigarettes, my chest unhitches when the songs of my adolescence play. I return to my friends on the dance floor to soften, if only a little at a time, around the anger that moved through me when I was younger. I breathe deep and sing along.

So much of life and art is a matter of perspective and focus; to create a happy ending is often to look away at the right moment. Today I choose to linger here, no matter that it will not last. If I could freeze my friends mid-dance it would be in these quintessential poses: Mark, both his hands above his head, as if he is doing the wave; Arizona, her head cocked to the side, one foot in the air, a sandhill crane mid-flight; Felicity, perfect in miniature, looking away, elbows and knees angled in shapes of grace. We raise our voices, though still inaudible beneath the bass that sends the cheap plastic ashtrays scuttling across the stage, say that we don’t behave, that we believe in a thing called love. Pause before the lights come up, before the sun rises in a few more hours.

• • •