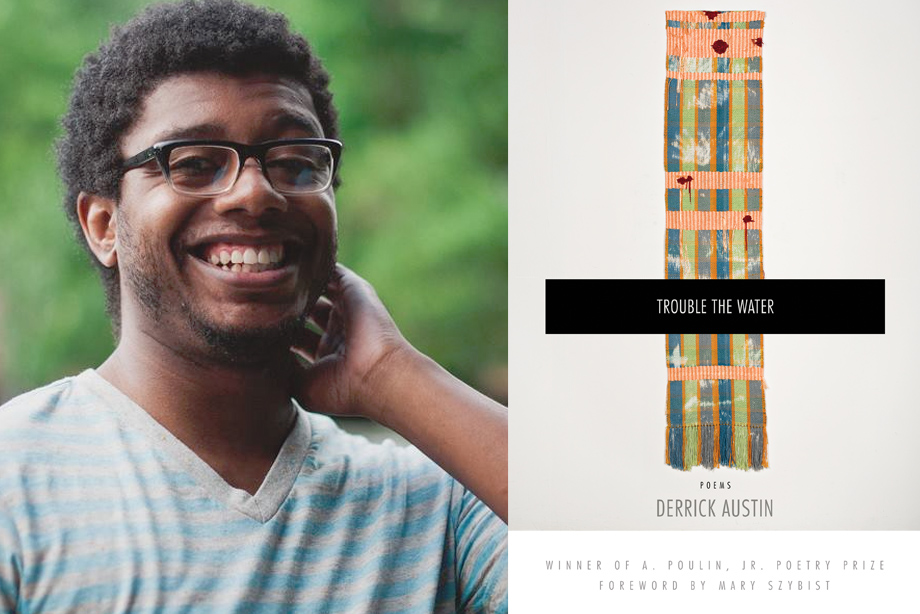

Award-winning poet and Functionally Literate alum Erica Dawson talks to Derrick Austin about race, religion, Florida, and his debut poetry collection, Trouble the Water.

______

Erica Dawson: Simply put, you slay: a hell of a lot of slayage at a relatively young age. What was the process for putting together and publishing Trouble the Water?

Derrick Austin: Thank you so much! I learned from the best. From when I wrote the oldest poem in the book (2009) to the book getting picked up (April 2015), it took about six years. Even as an undergrad, I knew I wanted to eventually publish a book of poems, but the manuscript didn’t start taking shape until my second year at my MFA, the semester before my thesis workshop. I’d played around with shaping the book earlier to no real satisfaction. For the most part, my thesis had the same shape as the book: four sections with most of the poems staying in those sections in different orders. The final section saw the most change. I didn’t know what to do with it until after my first Cave Canem retreat in 2014, and some expert advice about manuscript ordering from dear friends. I started sending it out that fall as an exercise in submitting books and because I was on my fellowship year at the University of Michigan so I had the money to send to contests. I didn’t expect it to get picked up so quickly. But BOA snatched it up, and it’s found a perfect home there.

ED: We’ve all heard the MFA vs. Screw the MFA debate. You attended the prestigious Helen Zell Writers’ Program at University of Michigan. What was your experience there?

DA: I always say this but I lucked out in terms of the other writers in my year. We all know how fraught MFAs can be for people who aren’t straight, white dudes. My cohort was thankfully pretty damn diverse. My cohort is lit. Coming from a small writing community at the University of Tampa, the group of writers I studied alongside were nothing short of a godsend. They really expanded my notions of what poetry could do and showed me things in my work I hadn’t noticed. We were all about the work, but also knew how to get down.

It would be disrespectful to be nothing less than truthful in my work. Why else be a poet? I want to write poems that endure, that say I survived, I thrived, and I didn’t look away.

ED: The poems in Trouble the Water often engage with religion. What drew you to this subject?

ED: The poems in Trouble the Water often engage with religion. What drew you to this subject?

DA: It’s funny how obsessed with religion I am. I wasn’t raised in a churchgoing home nor did my parents really talk about religion. But I fell into it in two ways. The first is through history. Other than English, history was my favorite subject growing up (I wanted to be a historian before I fell into poetry), and my way into different eras was through culture, particularly religion and art. The second reason is that I came up during the Bush II years. So there I was, a closeted kid, obsessed with religion and history watching the news run wild with evangelical Christians advocating for my erasure from society or my death. Writing about religion is my way of claiming such endlessly fraught, endlessly complex and rich material.

ED: Trouble the Water, at the same time, also explores some of our most earthly concerns, most notably racism and homophobia, issues so prevalent in our culture, many people have turned a well-informed, rather than blind, eye away from them. You, however, don’t shy away from this material at all. There’s such courage in your poems. Where does that courage come from?

DA: I think for me, the question is how can I not be? There are folks out here writing about their families, friends, or loved ones, which is difficult work. There are folks who have been abused trying to write into that trauma. There are people in other counties who die for what they write. There are folks fighting and writing to survive. My life has been extraordinarily privileged and blessed despite living in a country as virulently racist and homophobic as this one. It would be disrespectful to be nothing less than truthful in my work. Why else be a poet? I want to write poems that endure, that say I survived, I thrived, and I didn’t look away.

ED: Speaking of social issues, you’re from Florida. Do you consider yourself a Florida writer?

DA: I do. The state has had a profound influence on my writing. The lushness of my poems owes so much to the landscape itself, which is overabundant nearly all year. The muchness of the sea, the flora and fauna, the atmosphere—always getting into your home, your skin. Even time is different in Florida. Thunderstorms are more punctual than people. Summer is perpetual. Despite near constant development, history remains palpable. Of course, there’s that large marker of time known as hurricane season. There are so many Florida writers who nourish me too, like Zora Neale Hurston, L. Lamar Wilson, and Lyrae Van Clief-Stefanon; even folks who set up homes for significant parts of their writing lives like Elizabeth Bishop and Tennessee Wiliams.

Go out and live so you don’t forget the world when you write.

ED: One of my favorite poems from the collection, “Blaxploitation,” is a tour de force of a sestina. In the book, you move effortlessly between traditional form and free verse. When you begin a poem, do you know where you’re going from the get-go? How much of the structure do you have in mind before you begin?

DA: Very rarely do I know how a poem will end up shaped. A lot of my work in revision is actually trying to find the right form or structure. For example, my villanelle “Summertime” came out of a poetic forms class I took with Janet Sylvester, but it was a revision of a free verse poem I’d all but given up on. It was really amorphous at the time but had, weaving through it, early versions of what became that villanelle’s refrain. It brought out what was already inside the poem and made it stronger. The rhyming couplets and the poem in mono-rhyme from the City of Rivers sequence are the only times when I explicitly set out to write in a received form because I wanted that sense of classicism and heightened musicality.

ED: Your work seems to be informed by too many poets to count. In your mind, how important is your reading to your writing?

DA: It’s so important and much more fun than writing, honestly. I find that often if I’m having a rough go of writing it’s probably a sign that I need to get back to reading or I’m not reading widely enough. That last part is key. Don’t just read contemporary poets. Don’t just read American poets. Don’t just read poetry. Read fiction, essays, graphic novels, history, science articles, fashion magazines, blogs—the world is so vast. Read widely but be discerning. Find what feeds you.

ED: What are you reading now?

DA: Robert Walser’s Looking at Pictures, a short essay collection from the early 1900s but the work feels so modern. Lively, often brief, exercises in art writing. The recent Merrill biography is phenomenal, and I’ve been slowly making my way through a bio of Herbert. I’m positively obsessed with Alexander Chee’s Queen of the Night. It’s opulent, tender, gorgeous, and such a romp (someone make it a miniseries!). And I just finished Chris McCormick’s debut novel Desert Boys. We’re in such a moment of phenomenal chapbooks and debut poetry collections too: Robin Coste Lewis’s Voyage of the Sable Venus, Rickey Laurentiis’s Boy with Thorn, Phillip B. Williams’s Thief in the Interior, Richie Hofmann’s Second Empire, Aricka Foreman’s Dream with a Glass Chamber, Laura Theobald’s edna poems. Let me stop. I’ll never end!

ED: Other than poetry, what makes you want to pick up the pen?

DA: Lately, it’s been essays. I’ve always been that nerd that enjoyed writing analytical papers, but I’ve been turning toward personal essays. I don’t want to write straight personal essays (I don’t think I’m that interesting), but I love blending the personal with things from the wider world like art and pop culture.

ED: You love Drake. If you met him, what would be the first thing out of your mouth?

DA: You know at the end of the Sense and Sensibility movie when Emma Thompson finds out Hugh Grant’s character isn’t married and she makes that sound that’s sobbing/gasping/screaming? That.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=88_tyulOQDE?rel=0]

ED: I met you when you were in college. If you were sitting in front of college students, what single piece of advice would you offer them?

DA: Remember to take care of yourself and live. Writing is important but so are the people who care for you and the world. Go out and live so you don’t forget the world when you write.

______

Derrick Austin is the author of Trouble the Water (BOA Editions 2016). A Cave Canem fellow, Pushcart Prize and four-time Best New Poets nominee, he earned his MFA at the University of Michigan. His poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Best American Poetry 2015, New England Review, Image: A Journal of Arts and Religion, Memorious, and other journals and anthologies. He is the Social Media Coordinator for The Offing.