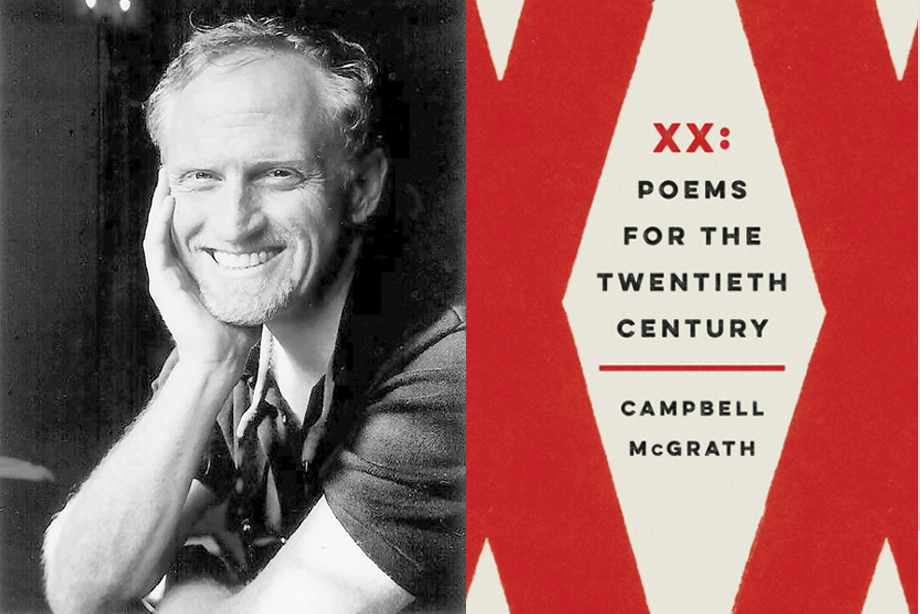

Campbell McGrath is the author of nine previous books. He has received numerous prestigious awards for his poetry, including a MacArthur Foundation “genius grant,” and a Guggenheim Fellowship. He has been published in the New York Times, Harper’s Magazine, the Paris Review, the New Yorker, Poetry, and Ploughshares, among other prominent publications, and his poetry is represented in dozens of anthologies. He teaches in the MFA program at Florida International University, and lives with his family in Miami Beach. I spoke with McGrath by phone about his new book, XX: Poems for the Twentieth Century, but first, because I am an Orlando writer, I had to address the elephant in the room. (Note: the interview has been lightly edited for readability.)

Miami has almost nothing in common with central Florida which doesn’t have that much in common with north Florida, but I definitely think of myself as a south Floridian.

Amy Watkins: You’ve said some pretty mean things about Orlando. In “Benediction for the Savior of Orlando,” you said it was a “city with the soul of a fast food restaurant.”

Campbell McGrath: I don’t have any mean things to say about Orlando. I’ve said them all already, that’s all. And they’re not really mean, they’re just sort of descriptive of the place. Really those things I’m talking about are about America in general. Orlando’s just a really typically American place because of its placelessness. All of Florida is, because there’s so little record of the deep history in Florida that everything we get is contemporary American stuff. If you go to the northeast, you have what our modern society looks like, but you also have these layers of the past going back. And you don’t really have that here. Everything sort of looks like it was built in the last ten months, and so all you get are corporate restaurants and stuff, and that’s not really anyone’s favorite version of America.

AW: It seems to be that way because the history of Florida isn’t really valued. It isn’t the history the rest of the country learns about in school. It’s not often what we see represented in art, so we don’t have much incentive to preserve our history.

CM: That’s true. There’s an essential component of kind of human place-based history that is viewing the place as in some way sacred or special or important, and Florida seems to kind of lack that altogether. And I don’t know why because it’s such a really cool place. That’s the thing. Chicago is built in the most boring place in the world–just a piece of the prairie by a big lake–but the city of Chicago takes itself really seriously and values its own history and its own past even though its place isn’t really that interesting. But Florida, which is a beautiful, fascinating physical environment, the people don’t really seem to value it because they let it be paved over into parking lots right and left and be torn down.

Like, as a thought experiment I’ve often wondered if there’s really a single building in the state of Florida that couldn’t be bought and torn down if the price was right. Like if Disney said they wanted to build a new theme park right where the capitol building was in Tallahasse, don’t you think the state would accommodate that and say, “Sure you tear that sucker down, you build that theme park and we’ll just build a new state capitol over here”?

AW: I don’t know. I live in Winter Park, which as a town is kind of proud of its history. Two or three years ago there was this old house they were going to tear down, and instead historic preservation groups spent a ton of money to literally put it on a barge and float it across a lake to a new location. But that’s an extreme exception.

CM: Yeah, but that’s what it takes! That’s what it takes to save stuff. It’s really expensive and difficult, but anytime anyone does it in Florida, everyone’s really happy. It’s like with South Beach. They’re like, “Thank God we saved South Beach as a historical art deco district!” But it only got saved because at the time the real estate was so benighted that everyone thought it was a joke. Everyone thought, “Who would ever want to live in this dump?” So it got historical preservation because of one or two activists, and now 30 years later everyone says thank god because otherwise it would be big faceless condo buildings. So, why Florida’s like that is because there are so few places where people have that sense of community and value of what they are.

But so much of the history of Florida has been fugitive people coming from a different place. Florida was just a temporary resting spot. Whether they’re snowbirds coming from Cleveland or whether they’re coming from Cuba, Florida wasn’t their space; they didn’t really put their value there. I understand that, but at the same time, we have so many people who really are Floridians that I don’t understand why we can’t do a better job saying, “Hey, Florida’s awesome. Florida’s cool. Let’s protect it. Let’s not let these corporate pirates constantly run roughshod over us.”

But really all of America has that problem. Florida’s just kind of an especially bad case.

AW: But you are a person who came to Florida from somewhere else. Do you think of yourself, at this point, as a Floridian or as a Florida writer? Have you claimed Florida as your own?

AW: But you are a person who came to Florida from somewhere else. Do you think of yourself, at this point, as a Floridian or as a Florida writer? Have you claimed Florida as your own?

CM: Yeah. I’ve lived in Florida longer than I’ve lived anywhere else. I grew up in Washington DC, so I lived there from one to 18, so 17 years, but everywhere else…I lived in Chicago three or four different times for a total of maybe a dozen years, but I’ve now lived in Miami for 22 years. It’s by far the longest I’ve lived anywhere, so definitely, yeah, I do. I one-hundred-percent think of myself as a Floridian, but I think Floridian makes no sense because Miami has almost nothing in common with central Florida which doesn’t have that much in common with north Florida, but I definitely think of myself as a south Floridian.

AW: I think a lot of the south Floridians I know would probably make that distinction. My brother-in-law grew up in the Keys, actually at mile marker 74, and you have that poem “Mile Marker 73.” I gave him Florida Poems when we were first getting to know each other, and he’s not someone who’s read a lot of poetry, but he loved that poem because it’s his home–almost literally–that place that means so much to him. People respond to that sense of place, I think.

CM: They do, even people that aren’t into poetry; they see it and they respond to it. So poetry is one of those ways of making a place sacred or special or memorializing, sanctifying a place. Art in general is. It’s not the only way, but it’s one way.

So I do think that writing a book like Florida Poems was personal self-exploration for me. Like, okay, I’m trying to understand this crazy place I moved to. But I also hear all the time that same story you just told me. Not like everywhere in Florida, but they often assign that book at UCF or UF, so for sure some freshman at UCF is amazed, like they never knew anybody wrote a poem about Florida. They never knew anybody wrote a poem about the Chuck E. Cheese because we kind of think of the world around us as so humdrum that it couldn’t possibly be worthy of that kind of thing, so everyone’s so surprised and interested when it does and maybe it makes them see their landscape differently. Hopefully.

AW: But the other side of that is that as a young writer I was warned about making my poetry too regional; like, you don’t want to be a regional poet. And yet sometimes those things that are very focused and specific really do get a strong response.

CM: Yeah, I would definitely disagree with that advice because, well, for a lot of reasons. I mean, I couldn’t disagree more with that advice!

AW: I ignored it completely.

CM: Well, I’m glad you had the sense to! I mean, I guess I can see why a teacher would say it kind of, but I think that teacher misunderstands what poetry is in a way. Poetry is about your own voice finding its way into the world. A lot of people think that poetry is like a foreign language you have to learn, like, “No, no no, it has to sound like this”–like you were learning French in French class–“No, no, no, what you did isn’t right, you have to learn this.” But that’s not right. The point is your voice, your experience needs to find its way into language and become poetry. It’s not mastering someone else’s version of it. So it’s your voice and if your life experience is rooted in a place, then the only way I would suggest you’re going to find poetry in yourself is to acknowledge that and find a way to get the language and the place to mesh and make it poetry. There are great poets that have nothing to do with place, but if that place-boundness is part of your voice and how you think of the world, then you have to deal with that essentially.

But the thing is you can do more than one! I mean, now I’m a Florida poet, but I didn’t grow up here. You know, I wrote a giant book about Chicago. You know, I’ve got poems in the Norton Anthology of the American West and I grew up in Washington DC, because I’ve written about, I write about landscape, human landscapes and physical landscapes that I feel I can connect to. I wrote that book about the Lewis and Clark expedition because you can go to a landscape and learn to experience it and understand it and write about it. It’s not, in other words, only one’s native landscape that one can speak of. You can speak of whatever you can connect your poetic voice to, which isn’t everything, but it’s many things.

AW: When I edit this, I’m going to come up with a really brilliant segue into talking about your new book, XX. Obviously it has a much broader focus than a book like Florida Poems, where you’re focused on a single place. How did you get started on it? Did you have to narrow down the focus over time? Did you have to start small and then broaden it?

AW: When I edit this, I’m going to come up with a really brilliant segue into talking about your new book, XX. Obviously it has a much broader focus than a book like Florida Poems, where you’re focused on a single place. How did you get started on it? Did you have to narrow down the focus over time? Did you have to start small and then broaden it?

CM: Well, the segue is, like what I was just saying about how there are some landscapes you can write about, and I was able to write about Texas but I’m not sure I could write about China unless I spent years there studying it. Well, it was the same way with these voices of the twentieth century. Some people I was really interested in writing about, I was able to get their voice down and some people I really thought I should write about, I wasn’t. In fact, some people I wasn’t even sure I did want to write about, like Pablo Picasso just sort of showed up in my head and started writing his own poems, in a way.

So, you throw your mind out there toward a lot of experiences and voices and ideas, and some of them your poetry brain will be able to turn on and make sense out of and some it won’t. That’s just a larger thought about the multitudinous of it.

I started the project because the book I wrote two books ago called Shannon on the Lewis and Clark expedition is written in the voice of this guy George Shannon, and it was a totally different thing that I’d never done before and it sort of became this historical narrative. I found it really interesting. I thought that it would be cool to tell a historical story from a voice that wasn’t just one guy’s voice over a short period of time, but what about different voices, like a chorus, over a longer period of time, and I couldn’t think what story that would be, so I thought, “What about the whole twentieth century?” You know, just kind of threw that out as a goal and a thought. So, I thought, “Well, I don’t really know if I’m going to get that all done, but I’ll start in as if I was going to do that and I’ll see where that leads.”

So I started doing it. And where did it actually start? Well, I didn’t write them in order, obviously. I bounced all around, but I did try to start at the beginning of the century. Because I was alive for almost 40 years of the century, I felt I knew that better. I felt I needed to study the beginning of the century. So, okay, what about Picasso? I know he’s a really important character to some people. Let me read about him. So I started reading about Picasso in Paris at the turn of the century and Matisse and modernism and Apollinaire and all that cast of characters. And it was very important artistically because it was the birth of modernism and modernism has determined so much of our intellectual and artistic history, but I just found them to be, humanistically, fantastically interesting, crazy characters. That notion of kind of inventing modernity was so interesting to me that I just kept writing poems about it and about Picasso because his voice was really strong in my head.

At one point I thought, “Well, maybe this book isn’t really about the whole twentieth century. Maybe it’s just kind of a Picasso book, maybe just like Picasso and people around Picasso,” and I just worked on that for a long time. I didn’t want it to be that but that’s where it was going for a while, and then I shook it out of there and it became a different kind of book. But I was just kind of going at different topics. I mean, for a whole year I was writing about Picasso but then I would switch over and say, “Well, you know what about the middle of the century. What about jazz and jazz characters?”

So I read a whole bunch of jazz biographies and listened to a bunch of jazz. I only ended up getting two really kind of small poems about jazz in the book, but I was educating myself because I’m a rock and roll person, not a jazz person, but it seemed important to American culture in the twentieth century to get my mind around it, so I got a whole education in it even though it ended up having a fairly small footprint in the book. But that’s the thing. I didn’t know. Maybe I’d write twenty jazz poems. I didn’t know. It didn’t end up working out that way, so it was kind of mysterious because there you are trying to get someone else’s voice down and you can try but there’s no guarantee it’ll work.

Our life is part of history. History is a collective expression of all of our time on earth…

AW: Was there anybody in particular that you really expected to have or wanted to have in the book that didn’t work?

CM: Well, there were. Like, in the clock poems–the kind of newsreel narratives–will kind of mention this person did this or that. A lot of those people that I mention just being born or whatever, they were people that I hoped to write more about. Like James Joyce and Yeats and Hemingway, that whole more famous crowd of English language writers never really get in the book. Often when we look at the twentieth century it’s that whole Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Americans thing, and I figured I’d write about those people but I never really could. They just didn’t really seem to take up the right space, so I just kind of stuffed them in those newsreel poems. A lot of those people I thought maybe deserved a whole poem, but I couldn’t really get it written. Jimi Hendrix I wanted to write a whole poem about, but I never could get it done.

AW: I like those “newsreel” poems. I think of them as sort of orienting the reader in the broad timespan: here’s what else is going on, or this is the context for whatever’s happening in the persona poems.

CM: Yeah, I think they end up being very important. For a long time I didn’t have them in the book and then I said, “I think I really need that.” They give the reader context and they gave me a way to do something with all these figures and ideas that I hadn’t found whole poems for, so it was actually very, very helpful. One of the last things I did was get those all organized and put in there.

AW: One of those poems is “Digital Clocks,” the poem for 1992, and that is a poem where the book shifted for me, maybe partly because I’m reading it as a parent. The personal starts coming in. Could you talk about the connection between the personal and historical in the book?

CM: I can’t imagine writing something about history that you didn’t have some personal connection to. It doesn’t have to be literal, but something imaginative. So, for instance, I wrote a whole book about a guy on the Lewis and Clark expedition, which I don’t have any literal connection to, but just imagining this 18-year-old guy wandering the great plains in 1805, I just was thinking about myself wandering that same landscape in 1985 and then thinking about my own 18-year-old son going out there and wandering around now, and there’s something about American male identity and the American west and some of those behaviors are the same, so I felt connected to it. And in the twentieth century I thought, “Well, I could write those first decades from a bird’s eye view, an objective point of view, but I am going to be born in this century, so I can’t pretend I’m not somehow personally connected here.” It seems like that’s kind of your duty as a writer to acknowledge that, so starting with 1962, the year I’m born, I start weaving myself in.

It’s two things: it’s kind of as an observer. I’m always an observer, but I now have firsthand experience to report on because really I did focus almost entirely on famous people. I’m the only non-famous person in the book, so it did give me a chance to talk about “here’s a kid walking to 7-11 to buy baseball cards.” I don’t talk about that with Picasso or Mao or anybody, so that’s one part of it.

AW: Well, you almost become the everyman character, that sense. You’re the American teenager in the 70s or whatever going to buy baseball cards.

CM: Yeah, I guess so. Another thing, the connection of images that for me made this book make sense was the memory in that poem in 1979, “The Nation’s Capitol,” about a summer I worked as a dishwasher at the National Gallery of Art, and I used to always look at these Picasso paintings. So then I’m going back and I’m writing about Picasso, and I didn’t know Picasso, but if you stood in front of those paintings and thought about them and tried to understand art and saw art as a powerful real thing in the world, then Picasso has shaped your world and touched you in a way. And then I learned about how Rilke, a poet who in later years came to influence me a lot, was himself influenced by Picasso and wrote one of his great elegies in the presence of that painting, and you start to realize, no, we connect to history. We think of ourselves as aloof from history. History is like a movie that’s playing somewhere else, but we’re just living our regular life here. No. Our life is part of history. History is a collective expression of all of our time on earth, and these were kind of literal ways of talking about that.

So there’s a poem about Anna Akhmatova at the beginning of the century in 1904, but then I have a poem about Joseph Brodsky in Venice in, I think, 1988. Well, Joseph Brodsky was my teacher in grad school at Columbia, but he was Anna Akhmatova’s student. So, in fact, I didn’t know Anna Akhmatova, but I can touch Anna Akhmatova and that sort of weird lost world of nineteenth century Russian society through this middle character, and it doesn’t have to be levels of removal because it doesn’t have to be a person that connects you; it can just be an idea or a feeling or a shared concern. So that’s what part of putting myself in the book was. One, it was that I’m sort of the only everyman character in there, and two, it was a way of saying, “Look, our lives are woven into this fabric.” That’s how it works. History is a little different than we think of it.

AW: That’s sort of a beautiful thing about art, that we can speak back to the past as it’s speaking to us in the present. And also leave something for the future, hopefully.

CM: That’s right. I agree with that entirely. Art stands outside of our normal time relationships. We are time-bound–everything marches forward one second at a time–but art kind of evades that equation or comes as close as anything human beings can do to evading that.

AW: How did you celebrate the millennium? Was it a big deal for you, the end of the twentieth century?

CM: No. I don’t think so. I’m pretty sure we celebrated with my in-laws. I mean, we would have had little kids then. They would have been like four and eight at the time, and I remember actually watching a fireworks display in Miami with my older son, who would have been like eight then.

It didn’t seem very important to me at the time at all, the twentieth century. One year’s the same as the next, you know, who cares. Centuries are arbitrary. They don’t exist. It’s a random grouping of time, and other calendars, like the Chinese calendar doesn’t even coincide with ours. Retrospectively they’re useful for organizing and thinking about events, but they don’t really exist, and of course, the thing that shows you what really exists are kids, because their lives are so…your kids lives are much more important than the arbitrariness of a century ending, and their timetable didn’t correspond with the end of the century. Like right now my youngest son is just leaving home, and this feels like the end of an era, whereas the twentieth century didn’t feel like the end of anything. Now is the important historical date for me. One’s own personal and biographical and family time table ends up being more important than these meta ones we’ve created.