We know now from the excavations

that Earth can blow hot enough

to melt a person’s brain to glass.

Vitrification, from the Latin

vitreum, for glass. They spoke that

language in Herculaneum, buying pears

from the market, strings for their lyres.

They must have cried out to God

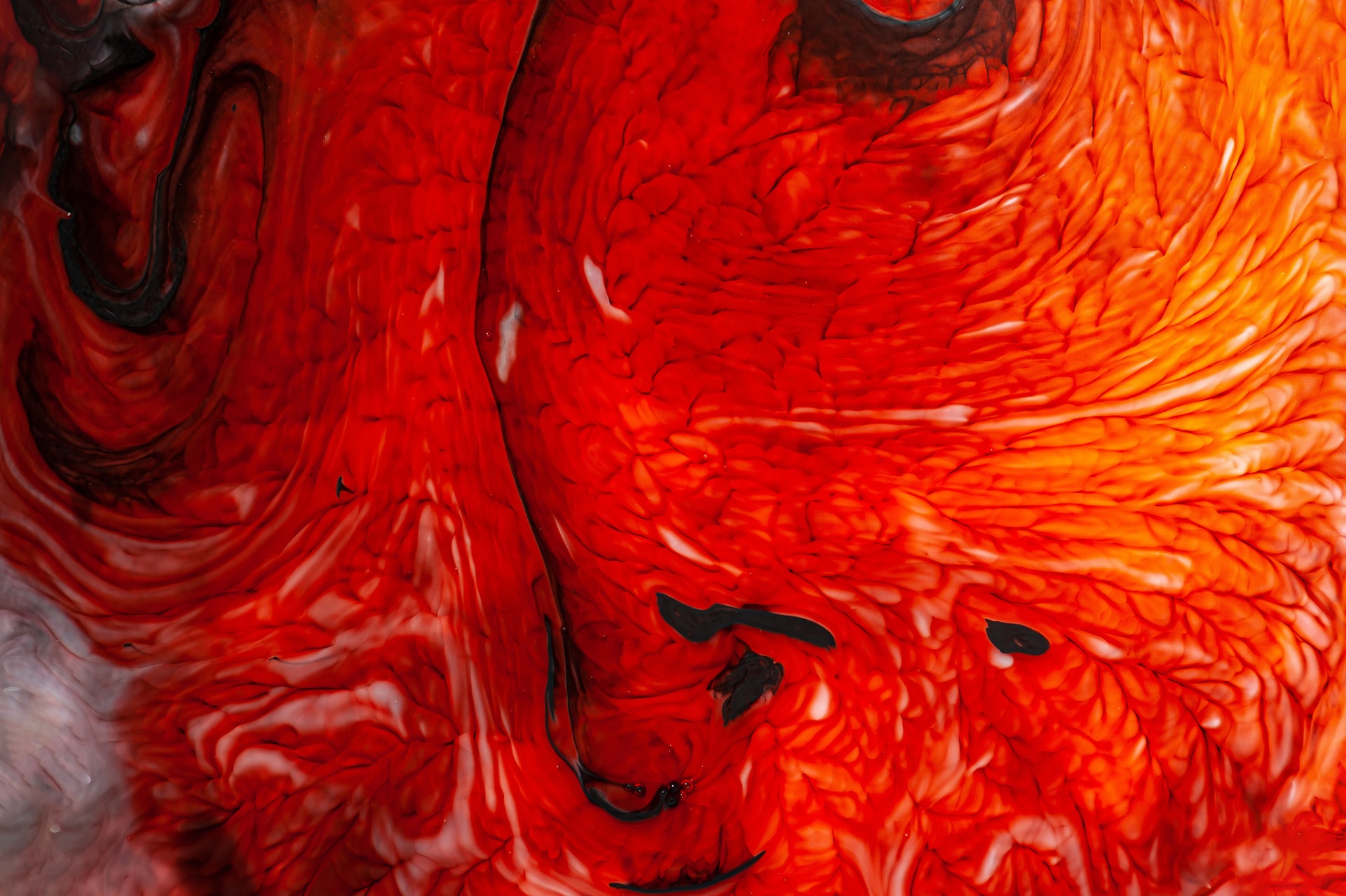

in that language when red death

cannoned from the mountain,

came for them at their altars,

in their kitchens, in flagrante delicto.

Think of that: becoming home

to an element that doesn’t belong in a body.

Glass not clear, as a mind should be.

Black as screams go when they can’t

push outward from a mouth, then

turn to ash against the teeth.

A brain complex enough to think the world

was safe—boiled down to a fragment,

obsidian and serrated at the edge.

This happened too at Dresden, February ‘45,

after three days of Allied bombs

taught the foreign a common tongue:

the language of fire. It must have felt

triumphant, that eruption from the jet’s belly

five miles above the earth. A plane called

Liberator flying home to the news reels,

horizon strung like a yellow ribbon,

bodies left for excavations.

This year, they stopped naming wars.

It’s all just war—uncountable noun,

like milk, leisure, sunshine.

Those of us without the bombs wonder

which of our organs are made of sand

and which, already, are turning dark and sharp.