Ritual is important. It adds ballast to a life. I remember the weight of the ceremonial bowls at Paestum. Their very existence was a mystery to me. The process of forging metal was still in its infancy. I was already old in that time, and I’d killed more men than all the temples held in a year. Some I lured onto the rocks off the coast of Capreae, where I’d crouch in the crags with my sisters. Others we’d sing to sleep before stealing onto their ships and cutting their throats. Each act made us stronger by virtue of the blood rite. We were daughters of the earth. In those days, I had little consideration for the race of men outside of my own survival. I considered them the weakest of species. It wasn’t until word of our fearsome nature changed the shipping routes and we were forced to move inland that I began to see what man was capable of. I could not fathom how a creature so fragile, so easily beguiled, could conceive and execute objects such as those bowls. They were perfectly round, and heavy, and polished to such a degree that they shone like the sun. They were superior to anything found in nature. They made me doubt my own perfection.

There were earthenware urns that held all manner of oil and perfume and depicted scenes of heroes and lovers.

“It makes them weak,” hissed my eldest sister. “Ripe for the plucking, like figs on a tree.” In the midst of that heady aroma, my eyes burning with the smoke of the altar fires, I walked the circumference of the room. The walls were covered with frescoes, which seemed to move in the haze. I lingered beneath an image of a man diving into a pool of water while, around him, other men played the song of Eros. I felt the brunt of my age then, and something else—the press of humanity’s knowledge on the barrier between our world and theirs. I knew, looking up at that diver, his body curved to slice cleanly through the water below, that the frescoes were more than mere adornment. They were emotion made manifest, a portal through which one might come to better understand a changing world.

We read the writing on the wall, as it were, and the pots, and the faces of the people in the temples and the marketplace both. We’d witnessed man’s evolution outward from something wild to something singular. It was like nothing we’d ever seen, this transcendence. Civilization had borne mankind to the precipice of Empire. In a few years, Rome would rule the world, and nothing would ever be the same. And our kind? We had been drawn down from the cliffs by a subtle shift in the magic that sustained us. Like all good predators, we would need to evolve along with our prey.

•

Now, my rituals are simpler. I carry them out alone, stripped of the pomp associated with the ancient world. I make the coffee; I pour it from the electric pot into a mug that was made by machines in a factory. If the early Greeks or Romans could see a factory, they would think it magic and attribute it to the gods. But a factory is merely one product of thousands of years of innovation. With its cartoon cat protesting yet another invention of man, Mondays, there is something of the Greek urn in this small object, though it does not mirror the quality of its predecessor. Unlike those vessels, this mug weighs nothing in my hands, even when filled to the brim with thick black coffee. I carry it out to the back porch of my little duplex and sit observing a mated pair of cardinals.

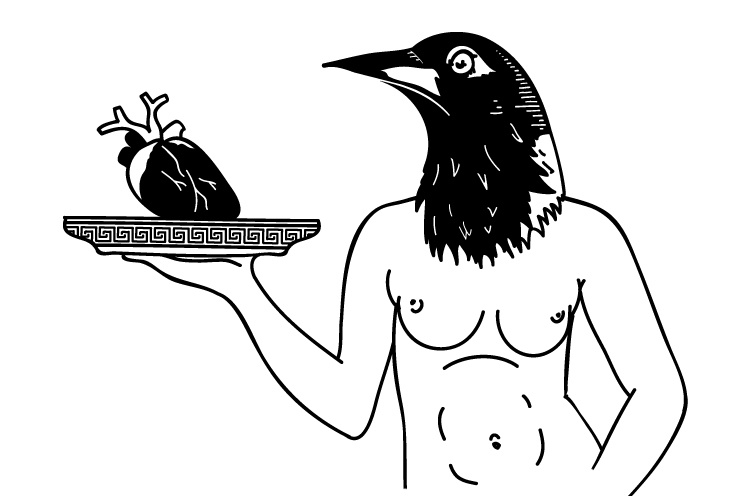

If you were to look up “Greek siren” in any world catalog, you would find yourself bombarded with images of mermaids. But as it happens, I am no daughter of the sea. In the ancient world, my sisters and I were most commonly aligned with birds. I call out a perfect imitation of the cardinals’ song. They return in kind. My neighbor’s cat comes through the fence to sit in my lap. I believe he is a little in love with me, or else a little in love with my birdcalls. We sit together, listening.

Eli has his own rituals. If mine can be boiled down to stillness, his are founded in motion. He is likely at the marina already, tinkering with the auxiliary or restringing the backstay. By 6:30, he has jogged a few miles and made himself a couple of eggs. Teeth brushed, hair combed, in jeans that are four weeks unwashed and up to his elbows in equipment, he’ll stay at the marina for another two hours before driving over to the small college where he adjuncts. He will make it to his 9 a.m. class with a few moments to spare. He will spend the next ninety minutes showing slides of the temples, and frescoes, and the urns to thirty undergrads who are just trying to meet their humanities requirement. I have never seen him take a drop of coffee, and the only time he’s ever late is when he stays over at my place and catches me singing in the shower.

•

Among my sisters, I was not the most beautiful. That distinction fell upon Aglaope, the youngest. Nor did my cleverness approach that of our elder sister, Peisinoe. It was she who discovered that some power could be drawn from a subject by merely diverting him from the true course of his life. As daughters of the earth, we were born with the ability to read a life the way sailors read the stars. To tear a man asunder from his destiny is an act tantamount to driving his ship onto the rocks. When we practiced the art of murder, it always began with a song. But the art of seduction was a dance, one that allowed us to study our victims up close. We learned to speak with honeyed tongues, to bend and fold our bodies into shapes that conducted pleasure like electricity. Though the power derived from such dealings was less than that obtained by bloodshed, it had the distinct advantage of lasting, sometimes for years. Men and women alike wasted away for love of us. We developed favorites among our disciples, and when these begged for mercy, we obliged in the form of a quick, painless death.

We took houses in all the great cities: Rome, Carthage, Thrace, Alexandria. The old faith fell out of fashion, and people forgot our names. All the better for three women alone and ageless to go unnoticed. We married for necessity, not love, and when we tired of our husbands, we dispatched them quietly in the night. Aristides, Florianus, Sabinus, Tiro: these men are unknown to you because I cut them off at the pass, forever altering the course of history by wiping their names from the annals. In this way, we passed entire centuries.

•

On Sunday evenings, Eli and I lie on the deck of his boat. Eli despises Sundays. He says they remind him of being a little kid and the grave difference between nights and school nights.

“Sundays would be okay,” he says. “But Sunday nights are the worst. The weekend is over; it’s too late to change anything. And you have a whole week of work ahead of you.”

In order to combat his misery, we try to come up with novel questions, queries no one has put to us before. Of course, I, who am older than all lines of inquiry, must give the impression that I am capable of being surprised by an interlocutor. I achieve this by asking Eli sly questions designed to get at the things I already know and adore about him. I never have to feign delight in his presence.

“What’s one thing someone could do in front of you that you would find painfully embarrassing?” I ask.

It isn’t my best question. I’m distracted by the fact that, in six days’ time, Eli will sail for California. He’ll be gone seventy-two days. If he leaves, if I can’t convince him to stay, I’ll be dead in two weeks.

Beneath us, the Cloud Chaser has been restored to her original glory. The sails are furled, and every inch of her twenty-seven-foot deck gleams with love and care. In the cabin below, spoons nest in the galley drawers. There is a sink, a stove, a small table, and a bed. I have stood in the temples at Paestum. I have beheld the library at Alexandria, and I have walked the halls of Versailles as a courtier. I am here to tell you, the cabin of the Watkins 27 is as fine a place as any I’ve seen.

“When someone I’m with tips poorly,” he says. “Especially if the service is good. I’ve been known to sneak back and amend a tip. Although that sort of embarrasses me too.”

We temporarily suspend our inquisition to admire the sunset. After a time, Eli says, “When I was a boy, I’d come out here with my dad. He’d tell me the sun was sinking into the ocean. When it finally disappeared beyond the horizon, he’d ask if I could see the steam given off by the hot sun plunging into the gulf.” Eli laughs. “You know, the funny thing is, I believed him so completely that I could see it.”

When I was much younger than I am now, people believed the sun was fetched from the sky and returned to the sea in a golden chariot. Later, it was said that the light of the sunset emanated from the garden of the Hesperides.

“Did you ever think the sun was something other than what it is?” Eli asks. In a time before time, before I learned to sing, when I was a squawking squalling drop of flesh in the miasma of creation, the sun was a fearsome thing. Later, as I grew into awareness and came to make out the distinct faces of those around me, the sun was a tool, a way to mark time. To answer honestly would be to take him by the hand and lead him through the history of the world, a history I share with the oldest things—the mountains and the sea. The sun is a ball of fire driven in a chariot, I’d say. It is a woman pursued by a wolf. It is a golden disk held aloft by a man with the head of a bird. It is a lover, a demon, a barge, a satellite. But what I say is, “The sun is a star, and all light is starlight.”

“Your turn,” he says when the last sliver of sun sinks below the horizon. “What’s the scariest thing you can think of?”

He doesn’t even pause to consider. “Doing just one thing for the rest of my life.”

•

During the Renaissance, my sisters and I settled in a small French village.

Peisinoe and I disguised ourselves as healing women and shared a little ramshackle house on the edge of a wood. Aglaope left us to marry a boy from the community. Near the decade’s end, we began to notice changes in our youngest sister. Her beauty remained unparalleled by the likes of human women, but with each year that passed, she grew slightly altered. Her hips widened. A fine lacework of lines appeared at the corner of her eyes. On the occasion of her husband’s thirtieth birthday, Peisinoe summoned her. There, in the single dim room of our little hovel, she plucked a lone silver hair from our sister’s head and held it before her like the indictment it was. It, in return, shone as if drawing all available light, from the cracks in the walls to the tallow on the table, toward itself. “How could you?” said Peisinoe.

Aglaope regarded us coolly. “I have moved beyond the bounds of our kind. I don’t expect you to understand.”

“Do you know what this means?” I said. “You will grow old. You will die. You. A daughter of the earth.”

“Children grow up. They leave their mothers.”

Peisinoe said, “You are nothing like them. You are a wild thing. You would allow death to come for you dressed in the clothes of a man?”

But for Aglaope, humanity had gained a foothold in her heart. She stood and placed a hand on each of our cheeks. We beseeched her to come away with us and forget this human who had bewitched her. The world has changed, we agreed, the magic has shifted once again into something dark and dangerous. Let us extract you. Let us figure out another way. Let it be together. We pleaded. We begged. But in the end, she walked away from immortality and returned to her husband. She grew old, but incredibly, she also grew in happiness. She didn’t die as a daughter of the earth, but as an old woman surrounded by her children and grandchildren.

•

On Friday, the day before Eli is to leave, I meet him at the marina. On the phone, he said he had a surprise for me. I walk right up to the boat. He is sitting on the deck. Above him, fresh sails hang from the mast. He grins like a cat that’s cornered something small and delicious.

“Well?” he says. I look up at the sails. His smile flickers. “What? No, Calandra.” He stands up and points to the deck.

“New shoes?” I ask. This is not the surprise I was hoping for.

Eli makes a frustrated noise before jumping off the deck. He takes me by the shoulders and backs me up a few feet. For good measure, he plants a kiss on my forehead. “You are a magnificent creature,” he says. Then he steps aside. From further back, I can see the entire side of the Watkins. Where it used to say Cloud Chaser, he has painted my name in bold letters.

“What do you think?”

This isn’t the surprise I was hoping for either. “It’s bad luck to rename a boat,” I say.

“Larks are good luck,” he says.

I remember my sister, growing old in her happiness. If Eli and I had met even a week earlier, before his father’s death put him on the path to California, he might have been the easy target I initially took him for. We might have had a chance at a life together. But fathers and sons, that’s old magic. Perhaps even older than me. He has never asked me to go with him, not once in three years, and he won’t. I can read it in him sure as the stars. He must make his father’s journey, and he must do it alone. That is his destiny. In the three years I have spent trying to steer him off course, he has never even come close to wavering.

Sometimes I wonder if Eli is actually the predator, and I am the prey. I have spent the span of the world doing one thing. I grow weary. It could be my time has come, that death has come for me in jeans four weeks unwashed. The age of magic is all but over; perhaps I have evolved past the point of usefulness. Yet I am also afraid, cowed by a long life and the burden of the history I carry on my back and the duty inherent in keeping that history. I was not the most beautiful of the sirens, nor the cleverest, but I among them remain the survivor.

•

Eleven years ago, I made my way from Newfoundland to Florida. I rented a little house on Treasure Island, a thin parcel of sugar sand and neon that stretches for three miles between the Intracoastal Waterway and the Gulf of Mexico. I’m about eight blocks away from the beach, which today is bordered by condominiums and multimillion-dollar cottages on stilts. Local legend has it that pirates favored the island throughout the seventeenth century. I cannot speak to those claims, but a hundred years earlier, Peisinoe and I, on our way out of the Caribbean, happened upon an expedition led by the conquistador Pánfilo de Narváez. Making quick work of him and his crew, we spent a few years living along the dunes and picking off Tocobaga warriors before working our way up the east coast of North America. Eventually, we landed at Roanoke.

Though it is not necessary to my survival to live near a coast, I’ve found that I’m soothed by the presence of the water. And of course, I have never quite lost my penchant for sailors. When I met Eli a few years ago, he was weeks away from defending his dissertation. Unfortunately, his work had been waylaid by the death of his father. He was in town helping his mother and sister arrange the funeral. He came into the salon where I work for a quick haircut on her orders. He needed more than a trim, he said. He wanted to look dignified.

I took his hand and led him over to the sink in the back. Though it had been more than a century, I was still raw from the loss of my sister. I hadn’t landed a mark in years, and honestly, I was out of practice. Still, something about Eli stirred my senses. As I lathered his hair, I sang an old song under my breath, one of the Delphic hymns. I worked his scalp with my nails and stole glances at his arms to check for goose flesh.

Leaning back into the sink, he wept. Quiet, without so much as a tremor, his eyes welled up, and fat tears rolled down his cheeks and into his ears. I worked my fingers into his scalp and tried not to focus too heavily on his exposed throat.

The next day he returned with an offer to take me to dinner, and I accepted. Over Cuban sandwiches and black beans, he asked me in Ancient Greek where I’d learned the Delphic hymn to Apollo. As luck would have it, Eli had spent the last six years earning a Ph.D. in Classics. I feigned ignorance of the mother tongue, and when he asked me again in English, I told him my high school choir teacher had favored the music of antiquity.

Eli’s sole inheritance was a rundown 1978 Watkins 27. “My dad was going to fix it up ahead of his retirement,” he said. “My mom hates sailing, she gets seasick, but my dad was convinced all it was going to take was her slapping on a couple of Sea-Bands and away they’d go. He wanted to live on the boat half the year and sail around the world.”

“You should sell it,” I said, knowing full well that he’d already invested the bulk of his grief in taking up his father’s project. “Boats are a lot of work.” Even then, I was becoming lazy in my diversions. And I was unsure. When he looked at me across the table, I felt as though he knew exactly what was sitting across from him.

“Calandra. You were named after the meadowlark. Was that on purpose? Did your mother teach you to sing?”

I am a daughter of the earth, I thought. I could sing before your kind had crawled out of the ooze. “Yes,” I said. “She did.”

It had been some time since I’d taken a lover. Peisinoe and I had parted ways for a time, as we were wont to do. This was during the Enlightenment, and we agreed to reconvene in five years’ time in Rome at the Coliseum. She never showed, but even before I set foot in the ancient city, I was certain she was gone. It took me another five years to track down anyone who knew her. Finally, an old woman in Barcelona said she’d known a young Greek girl, the frequent companion of a woman who often dressed like a man. One day, the woman donned her best coat and trousers and told the girl she was going out to find work. The woman went to the docks, boarded a ship, and never returned. The girl would go to the port each day and sit with her eyes fixed on the horizon. She grew grizzled and haunted-looking; it was unlike anything the old woman had seen. Almost as if the girl were aging at a rapid pace. Within a fortnight, she was dead. My eldest sister, daughter of the earth and cleverest among us, had finally met her match. Legend has it that a Siren shall live only until someone hears her song and passes by unmoved. When death came for Peisinoe, it wore the clothes of a man.

•

That night, Eli and I lie in the cabin of the Watkins. He is positively giddy with anticipation of his adventure. When I don’t return his enthusiasm, his brow furrows with concern. “Hey,” he says. “I won’t be gone forever. It’s only a few months.” I nod my head, the eons flashing across my mind’s eye like heat lightning in a storm. Perhaps it’s for the best. The burden of my nature was heavy even when I was one of three, and in my solitude, it threatens to overwhelm me. Rest would not be unwelcome.

And yet, there is a part of me—perhaps human, perhaps not—that desperately wants to survive. I run my fingers along Eli’s jaw and lightly trace the curve of his neck, the outline of his throat.

He takes my hand and holds it in his. In the span of silence, I imagine him pressed up against the curtain that hides my true nature. It is so thin that I can make out every curve of his body, the shape of his eyes, nose, and mouth.

“Calandra?”

I imagine something new in his voice, something I’ve never heard before. Fear.

“Don’t go,” I say.

“You want to know why I asked you to dinner after you cut my hair,” he asks.

“Why?”

“Because I recognized something in you. Loss. And I’ve never pressed you on it, Calandra, because I figured you’d tell me in your own time. Maybe you will. But the thing I’ve always liked about you—about us—is that I don’t have to explain. Because you already know. You’ve always just known.”

An involuntary shiver runs through my body, a flutter of my predator’s heart, and in that moment, I cannot say whether it is for fear of what I might do or delight.

He says, “Will you sing to me?”

Will it make a difference? I want to ask but don’t. I sing him a Delphic hymn. As soon as he falls asleep, I sneak off the boat and head home, afraid of the consequences if I stay.

•

On Saturday, I wake earlier than usual. I make the coffee; I pour it from the pot into a mug. Carrying it between my two hands, I make my way out to my back porch and settle into a chair. I’m thinking of Eli. I am thinking of Aglaope, and Peisinoe.

Long ago, when we stood in the temple, it seemed to us that mankind alone had accomplished the greatest feat of the ages by stepping out of the wilderness. But man was not alone. When we crawled down from the cliffs, we left a little bit of our original nature behind. As we moved to adapt alongside humanity, our stories twisted and twined until they were nearly indistinguishable from one another. And so there is something wild in the heart of every human, and there is something human in me. And what is more human than hope? A hope for a heart transformed, and the possibility of a good death. The light in the east tells me I have time. I can make it to the marina before Eli leaves. I can still see him off. I can sing him one last song.

Rising, I almost fail to notice the silence. Not a single note of birdsong rends the air.

I whistle. Nothing.

Looking out over the yard, my eyes come to rest on a single bright spot of red in the grass. I drop my coffee. I run.

I find his head first. The eyes are open and bright. A few meters away, I find his body. The breast has been torn open. I pick up the pieces of him. Above me, there is a furious fluttering. I look up to see the female cardinal beating a wild dirge with her wings. I coo. I cajole. “Come down little sister,” I say. “It’s all right.”

It is not all right.

If I could catch her, I could bring her into my house. I could offer her shelter. But she is a wild thing, just as I was before the long years tamed me, and she is right to fear me. She knows what I am.

I bury her mate’s body and head. I walk back to the porch and recover the mug.

My hand is on the doorknob when I happen to look down. There, on the stoop is an offering. It is the cardinal’s heart. In my palm, it is warm and wet and heavier than it looks. The air is quiet once more. The female won’t return, not now. I am crouched on the stoop, one hand on the doorknob, one hand holding the heart, my body perfectly still, suspended in the violence of what I am.

A daughter of the earth. I could shutter the house. There is room for a coffee pot in the galley of the Watkins. Maybe even a cat. One more ritual, beginning with one more song. For the first time in a long time, wildness overtakes me. I put the heart in my mouth and tear it to pieces.