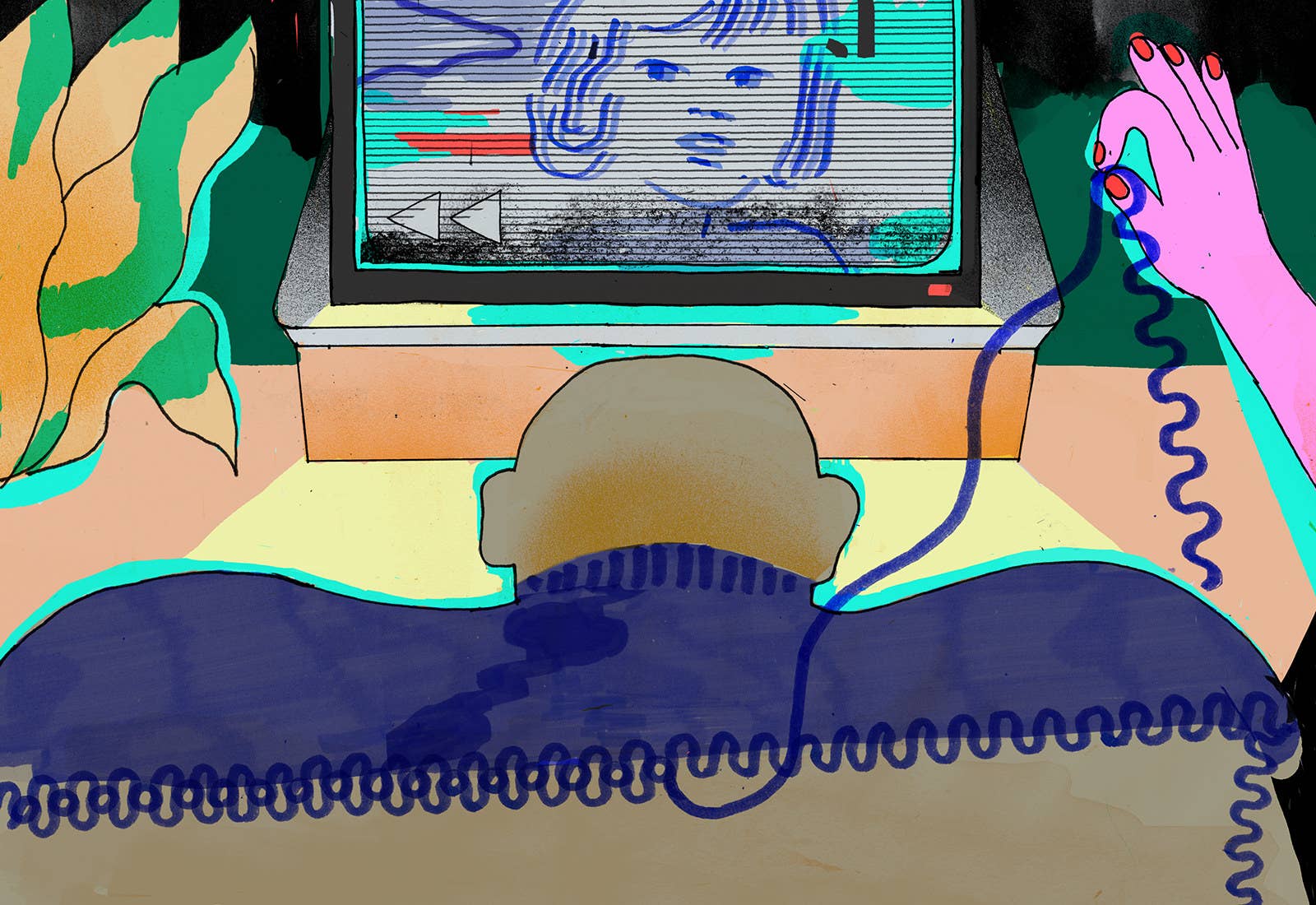

Marnie had to get the bloody sweater off her father. He was crying, watching a twenty-year-old camcorder video of himself with Marnie’s mother — footage of the two of them riding a giant mule at a county fair. He kept rewinding the video back to the scene where they jumped off of the mule in tandem. He’d pause it there, so it looked like they were being sucked upright into the air, the two of them levitating beside the mule. Then he’d press play, then rewind, then pause. Her father found this activity gratifying. So much so that he’d recently quit his job to do it full-time.

Her mother had run off with a jazz musician several months ago, during the first week of Marnie’s junior year of high school. She hadn’t left contact information or been in touch since.

Marnie considered trying promiscuity as a distraction from grief, but was hesitant. It felt like her mother leaving increased Marnie’s chances of an unwanted high school pregnancy. “Think about it,” Marnie told her friend. “Say four girls hook-up with four football team members under the bleachers Friday night. All four guys pull out slightly late, but only one of the four girls gets knocked up. It would be the girl whose mother had abandoned her.” Marnie had the sense that stigma did not readily consent to solitude. The disgrace of her mother leaving was a lodestar. A GPS that sent Marnie’s coordinates to further misfortune.

Wasn’t magic just the act of appearing or disappearing, suddenly?

She figured traumatic desertion probably increased one’s fertility. There was a magnified picture of cellular division in her biology textbook, and below it the book’s previous owner had written GREED in red marker with teardrops coming off the word, like the letters were sweating. Maybe whoever drew this hadn’t meant it as a caption for the photo, but Marnie felt that was the best interpretation. She could imagine the dumb, animal brain of her body thinking it had figured out a way to solve the void in her family. One person left me? No problem; I’ll make another!

It was best to stay vigilant against supernatural interventions like pregnancy, which seemed as eerily magical as her mother’s overnight departure. Wasn’t magic just the act of appearing or disappearing, suddenly? The sadness that arrived when her mother departed played tricks on Marnie. When her father had told her, he’d said, “Children shouldn’t glimpse such uninhabitable honesty”; in his despair his bathrobe had fallen a little too open. Although she didn’t think of herself as a child, the statement seemed apt in regard to many aspects of her life. Panic now came upon her at school in sweaty fits, and when the urge to vocalize grew too intense to suppress, she’d burst out in laughter to camouflage the hysteria. Marnie kept two halves of a broken pencil in her backpack to hold out as prop evidence as she cackled and shook. I’m always breaking pencils and cannot help but laugh at the frequency! Fractured wood, how hilarious!

Pretending to laugh produced the same abdominal soreness as repetitive vomiting and made her smile muscles hurt. Between classes she liked to go into a bathroom stall and stretch the flesh of her cheeks out like pizza dough. As she kneaded her face, she’d remember a song from childhood whose lyrics pretended English words all became Italian words with the suffix of –uh. It had been funny when she was little, but its lyrics lacked cultural intelligence. And it was mean, its main character ‘uh big-uh fat-uh lady-uh.’ She saw now that the song was awful.

Perhaps this was the work of growing up, Marnie thought: increasing the ability and speed with which she could recognize the bad. She thought often of Puffy, a hamster she’d owned for two years in elementary school. The day they’d brought it home, her mother had washed it in baby shampoo so its fur had a floral smell. Marnie played with Puffy for hours, and then he defecated on her lap, which was a shock. Marnie hadn’t realized the hamster was going to defecate. Ever. She’d wept for hours, became withdrawn for weeks. Nothing was perfect.

Marnie’s friend Jana felt her boyfriend was perfect, though. “He’s so good,” she was always telling Marnie. The boyfriend was older and had been fired from a fast food restaurant over allegations of theft from the cash register, though Jana staunchly maintained his innocence. Marnie had the feeling that over time, problematic information about him might come to light. Jana had recently gone on birth control, and she was very alarmed at how small the pills were. “Do you see?” she’d asked, holding one out to Marnie on the tip of her finger, “how microscopic these are? I don’t think they’re even big enough to work.”

“Yeah,” Marnie had agreed. “They should be way bigger.”

Perhaps this was the work of growing up, Marnie thought: increasing the ability and speed with which she could recognize the bad.

Her mother’s abandonment seemed to have given Marnie access inside a whole carnival tent of unwanted discoveries. For example, she learned that Gam-Gam, her paternal grandmother, had never been in favor of her parents’ union. Gam-Gam had a lot of opinions. She visited the two of them a few weeks after Marnie’s mother went away.

No matter what Gam-Gam was saying, something about the tone and volume of her voice made Marnie feel like she was being ordered to mop a floor. “Of course it ended in disaster,” Gam-Gam yelled at Marnie’s dad. “You married for love! Next time set yourself up for success,” she encouraged, adding that he was welcome to borrow the recipe she’d used for her own marriage to his father, now forty-eight years strong: he needed to seek out a tepid emotional connection, a person whose skill sets and interests were in direct opposition to his own. “Because happiness isn’t going to cut the mustard,” Gam-Gam continued. “There is no way in hell.”

In terms of gossip, Marnie found out, dying was preferable to leaving. The dead can be hard to speak ill of, but no one had that problem regarding her mother. “I heard your mom is a slut,” a boy said at lunch. “Are you a slut too?” She couldn’t tell if it was a bullying tease or a straightforward inquiry. When she didn’t answer he began eating a meatball sub at a fast-forward pace. Marnie wasn’t sure why, but she’d held out a napkin out to him. He didn’t take it. Instead he wiped his forearm across his mouth and got sauce all over his skin. It looked like an injury. “What are you staring at?” the boy asked. Marnie didn’t answer but continued to watch him. It was strange to see a person who appeared to be hurt eating instead of screaming or weeping. She wished her father would try eating. Due to the bloody sweater, her father now also seemed to have surface wounds on his body.

After he had stopped going to work, Marnie had waited up one night until she heard his snores. He liked to pass out on the ground in front of the TV, watching the tape, then wake up and resume. He often watched it while lying on the ground in corpse-posture, limbs sprawled out, seemingly the fallen victim of a swift homicide. He’d wake up with a red-patterned indention on whichever of his cheeks had pressed against the carpet all night. Every morning half his face appeared cloaked with a mysterious birthmark.

Marnie had taken the tape out of the player, gone outside and thrown the tape in the creek that ran out along the back acreage of their property. When she came back inside, her father was awake and the same tape was playing on the TV. “I have several copies,” he said, “but where’s the one you took?”

“This video thing,” she’d offered. “You’re trying to do something with time?”

The dead can be hard to speak ill of, but no one had that problem regarding her mother.

“Do you see that?” he’d asked, pointing to the screen. “Your mother’s eyes? Don’t they seem to be looking into the future? Did she think our love was destined to fail even then?” Marnie had glanced at the paused image. Was her father talking about her mother, or about the mule? Both looked unimpressed and a little hungry. They were squinting even though there was no sun.

She’d turned off the TV and they’d stared at each other. “What are you wearing?” she’d finally asked him. It was a small white angora cardigan, buttoned but stretched beyond capacity; it ended several inches above his midriff. “One of the only pieces of clothing your mother left behind,” he said. “I had to put it on. Does that seem crazy?”

There was a free calendar from the credit union, several years old, that her mother hadn’t thrown away because it had a motivational quote on each month’s page. Whenever a question puzzled her, she used to open it and read a quote aloud by way of a response. Marnie had looked at her father and flipped to June: Unhappiness is in the eye of the beholder, it read. “I wouldn’t use the word crazy,” she’d answered.

When she told him the tape was in the creek, he’d suggested they walk there and go fishing for a few hours. It was three a.m. on a school night. Marnie didn’t like fishing; it seemed like fishing might be the only thing more miserable than standing in the living room with her father, which made her interested to try it. She liked challenging herself this way: On any given day, how much discomfort was she able to bear?

They took one reel with a lure and Marnie watched on, her father having promised to throw back anything he caught. But when the line did pull and he tugged up a bass, this vow proved hard to keep: it had swallowed the hook. The hook was caught on something deep inside the fish. She had to turn away while her father struggled to get it out. In the dark the blood looked like ink. The average-sized fish was leaking so much of it that in another context it would’ve seemed comical — her father’s arms and her mother’s sweater looked like they’d been drenched in gallons of fish blood. “Okay,” he’d finally said. “It’s good as new.”

Marnie had disagreed. They’d watched the fish’s body float out across the water like a tiny canoe. Then it gave a twitch and they both gasped: “There it goes,” her father said. “It’s going to swim away.” But it was just a death lurch, or maybe something from below had poked it. “We’re not going to find the video tape,” Marnie said.

“Hey,” her father added, his face perking up with suggestion. “Let’s go inside and watch it?”

On the walk back to the house, she remembered a day, unremarkable, when her mother had worn the sweater. She knew her father wasn’t going to take it off willingly. He’d continue to wear it, and when the blood dried he’d act like any problem Marnie had with the garment had been reconciled. She’d have to take it off of him one string at a time, unraveling a little bit of it each night.

“Can we let the video go to the end this time?” she’d asked him. Her father wasn’t interested in the most terrible event captured on the tape, which played out in the shot’s farthest right corner during the final moments of the recording.

She liked challenging herself this way: On any given day, how much discomfort was she able to bear?

The last three minutes of the tape went like this: He and her mother jumped off the mule. They approached the camera and began talking about their upcoming wedding. But in the very distant background, the mule made a slow but immediate beeline out toward the palm tree lawn and started to give birth. “Why were you riding a pregnant mule?” Marnie asked. “Not just one of you but two? That seems cruel.” Maybe, she reasoned, if her parents hadn’t given a pregnant mule trouble they’d still be together.

This made Marnie hope her parents hadn’t made a video recording of her mother giving birth to her. It wasn’t the thought of the delivery on tape that made her skin crawl as much as the idea of her father pressing rewind and then play, again and again, reversing nature’s decision. It seemed like the type of obsessive careless action that, under certain conditions, could cause Marnie to cease to exist.

“Did your collective weight induce the mule’s labor?” Marnie questioned. “Be honest with me!” Her father cleared his throat and pressed rewind. On the television screen, the mule’s faraway body retracted the suggestion of life it had been pushing out. When the creature turned around, it seemed to have changed its mind. ●

Alissa Nutting is author of the novels Tampa and Made for Love, and the short-story collection Unclean Jobs for Women and Girls. She is an assistant professor of English and creative writing at Grinnell College in Iowa.

For more information on We Can't Help It If We're From Florida, click here.