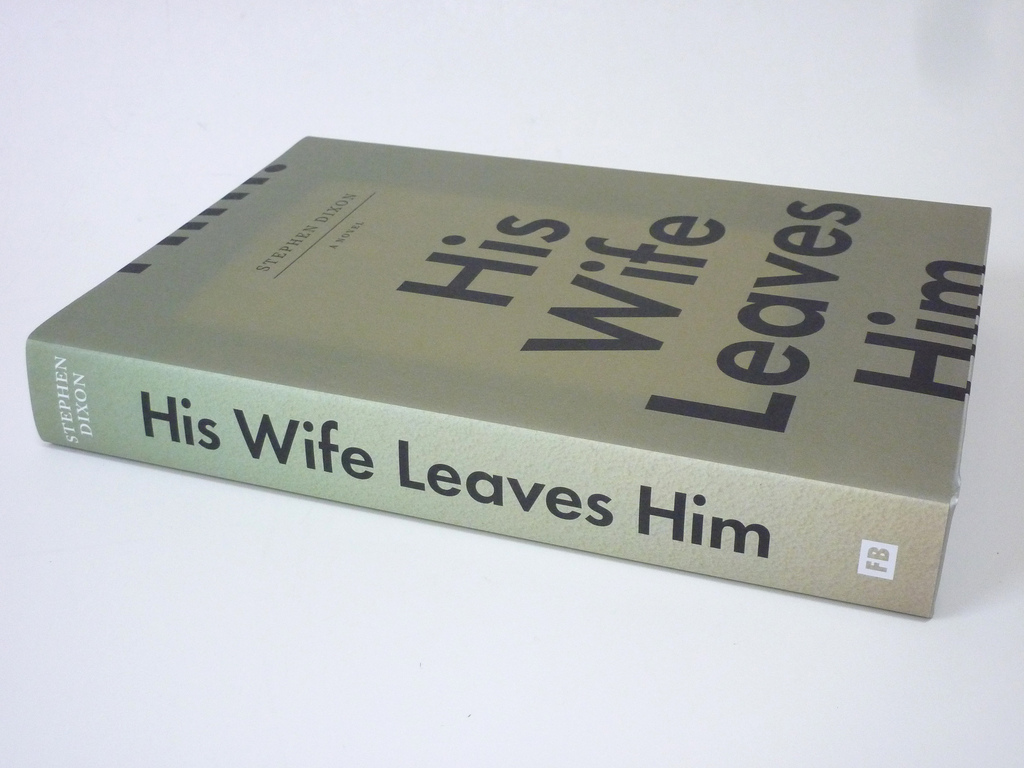

An excerpt from the novel, His Wife Leaves Him

Editor’s note: If you know Dixon’s work–and you really should–you’ll enjoy this and, hopefully, buy the book and enjoy it too. If you don’t know Dixon’s work–and there’s a lot to know (some six hundred published stories and fifteen or so “novels,” though what exactly constitutes a novel in the oeuvre of Dixon is questionable)–you’re in for a real treat. He is–and I say this as a fan, long-time reader, and acquaintance of the man–one of the most innovative American fiction writers still at work. –James Fleming

Someone knocks on his classroom door. “Come in,” he says. It’s his department secretary. “Excuse me for interrupting your class, but you have an urgent phone call.” “My wife?” “No, a man.” “He say what it was?” and she says no. “Let’s take a ten-minute break now,” he tells the class. “You’ve heard; I got what’s supposed to be an urgent phone call, so if I’m not back in twenty minutes, let’s say, or make it thirty, next week’s writing assignment and the readings from Short Shorts will be posted on my office door.” “Where’s your office again?” a student says, and he says “This building, room four-forty.” “Does that mean we won’t be critiquing my story today?” another student says. “Because last week we also never got around to it,” and he says “I don’t know; please, let me go,” and he leaves with the secretary. “The caller didn’t even hint what it could be?” he says, as they walk to the department’s office. “Maybe he meant ‘important’ instead of ‘urgent,’ and it’s good news; an award or nomination of some sort for my last book. Well, one can always dream, right?” and she says “No hint; nothing. He just said to get you.” It’s someone from a local hospital; his wife had a stroke while riding an exercise bicycle at a health club and was taken by ambulance to Emergency and is now in ICU. “Took us a while to find out who she was, since nobody at the club knew which locker her belongings were in, and then to reach you, since she’s unable to speak.” “Oh, geez; she only joined that all-women’s club last week. Before, she was in mine. I’ll be right over.” She’s hooked up to tubes and monitors and something to help her breathing, seems to be awake. “Darling…sweetheart,” he says when he first sees her. “I’m here; you look fine; you’re going to be okay,” and takes her hand, but she doesn’t give any sign she knows he’s there. He sits by her bed for as long as they let him—fifteen minutes an hour for about ten hours a day; sleeps on a recliner by her bed for a few nights after she’s moved into a regular room. She gets stronger and more alert, goes through several weeks of in-patient rehabilitation, and comes home. She’s paralyzed on one side of her body but gets back most of her speech. “Look at me,” she says. “Four months since my stroke. I still can’t do a thing for myself or anyone else. I can’t hold anything without dropping it. I try to walk with a walker, I get three feet before I feel I’ll fall.” “Look, that was some blow you took. It takes time, sweetie, time, and you have to admit you’re a hell of a lot better than you were a month or two ago. And from when you were discharged? —We won’t even mention what you were like when you first went in. I couldn’t have hoped for anything so quick. But back to normal? The doctors say what?—a year, year and a half from the time you had the stroke—but I’m sure, the way you’re going, it’ll be much sooner.” “I’m sorry I’m such a burden on you,” and he says “What are you talking about? I’m happy to do whatever I can for you. Really, it’s a privilege to help you, my darling.” “Oh, I know it’s not—how could it be?” And he says “Have I ever complained once? You know me. I can be impatient and I get frustrated easily, but I’ve never been angry at you concerning your condition or that it’s taxing me in any way or keeping me from my work. What can I do to make you believe me, get on my knees?” and he does and hikes up her skirt and kisses her kneecaps, and she laughs and says “All right, stop, I believe you; I just needed a bit of convincing. Thank you.” So he can teach and hold office hours and do other things like write at home and shop and go to the Y to swim and work out a few times a week, he has caregivers looking after her every weekday afternoon. Weekends, if one of their daughters doesn’t come down from New York, he takes care of her all day himself. Sometimes it’s hard—getting her started in the morning, lifting her out of bed or into a chair, her incontinence a couple of times a day, cleaning up when she spills some drink or food or knocks a mug or plate off the table—and he thinks, “God, not again; I don’t know how I can do this anymore, but what’s the alternative?” or looks at her and thinks “Come on, you’re a smart woman, so show some brains. If you know you’re not going to be able to hold something, have me do it for you.” Or “If you know you’re about to shit or piss, tell me, so I can get you on the toilet or a bedpan under you, because you just make things worse,” but never says anything or makes any kind of face that shows how he really feels. All he says is something like “That’s okay, that’s okay, don’t worry about it; this is what paper towels and those latex gloves are for. Complete recovery takes time, as I’ve said, but you’re definitely getting there. Each day there’s a little improvement, I mean it.” “I wish I could see it.” It takes a few more months for her to work herself up to walking from their bedroom to the living room with just a walker, and a couple more months, about the same distance with just a cane. “You see?” he says, “what did I tell you? Although the truth is, which I didn’t want to say a while back because I didn’t want to discourage you, I never in a million years thought you’d progress this fast,” and she says “I actually do now feel things are finally getting better for me. I can’t wait till I no longer need anyone’s assistance, and then can walk without the cane.” He always walks beside her in case she starts falling, which she sometimes does, and he always catches her. She also doesn’t drop or spill things as much, and goes for days without being incontinent and weeks without an accident. When she does have one, she says things like “Oh, dear, look at the trouble I’m causing you; I’m so sorry,” and inside he’s seething, thinking of all things he hates doing most—piss, he can handle—but this; it’s so goddamn messy and time-consuming. But after one accident, he says “Damn you, can’t you give some warning when it’s about to happen and then hold it in till I can get you over the potty?” and she starts crying and he says “Don’t; stop it; just let me get the job done. And I didn’t mean it. I’ll never say anything like that again.” “But you’d think it,” and he says “No, I wouldn’t. It just came out, as if it wasn’t even me saying it. It had nothing to do with my being on my best behavior and suddenly losing control. I know you’re not responsible for what happened and you want to make things as easy for me as possible, and for a few seconds I was a total putz. Please forgive me.” “Okay, though I wouldn’t blame you for thinking it. Just hearing it is what makes me feel so bad.” She has another stroke, same side, a few months later, shortly after she began walking around the house with a cane without him having to stay beside her, but this one a lot worse. She recovers much more slowly than she did after the first stroke, goes through months of physical and occupational and speech therapy, first when she’s in the hospital and then as an out-patient, but she still can’t walk a step with a walker, even with his help, and spends most of the day in a wheelchair. “Try pushing it yourself,” he says, six months after she comes home—he wanted to say it sooner but held back—and she says “I can’t. I can barely feel the wheels when I try to grip them. I have no strength left for anything, and my speech is still so terrible that I’m not even sure you understand a word I say.” “Oh, I understand; I’m hearing everything you say clearly, and I’m not being sarcastic. But just try, once, pushing.” “I have. Lots, when you weren’t looking. Maybe I need to exercise my arms and hands more, but I don’t have the strength for that either.” She’s depressed almost constantly. Getting up: “What am I getting out of bed for?” Eating: “What’s the use of food? Just means more time on the toilet and all the problems that go along with that.” Working on her voice-activated computer: “I used to be a thinker, and now I can’t think straight. And there’s no project I once wanted to do that I’ll ever be able to finish.” Talking to their daughters or her friends on the phone: “Tell them I’m busy or sleeping or too tired to talk. I just have no desire for petty talk or conversation.” Sex: “No feeling: no interest. I know, though, how much of a deprivation it is for you.” Going out for lunch or what he calls “a walk”: “Why should I let myself be the object of other people’s stares and pity?” Listening to books on tape: “I can’t keep up with the story or lecture anymore.” Watching a DVD movie at home: “They used to be enjoyable when I was healthy and had some hope of recovery. Now everything I do and see tells me how sick and feeble I am and that I’m only going to be worse.” When he says “Come on, give me a smile, will ya?” she says “Would you be smiling if you were me, even one on demand?” “Sure, because, you know, it doesn’t help either of us if you’re always bitching about your condition and how weak you are and moping around all day with your all-suffering down-in-the-dumps face. I’m sorry: that was mean.” She’s already crying, and he says “Okay, okay, I said I’m sorry and I meant it. It was stupid of me.” “Oh, you apologize and you apologize and you apologize, but don’t once more tell me you didn’t mean what you said. As I’ve already told you: I’m a drag and a drudge and you should get rid of me,” and he says “And then what would I do with myself? Can’t live without you, so shove that thought right out of your head.” “I don’t believe you. But for now, just to make myself feel a little bit better and to show you I don’t think of myself as utterly hopeless, I’ll accept it not as a lie.” He bends down—she’s in her wheelchair—and hugs her and kisses the top of her head. She hugs him back around the waist and says “Thanks. I feel better but I’m not going to smile, even if what I just said could be construed as funny. But you really would be better off if I were gone and you were free to take up with another woman, one who wasn’t in a wheelchair.” “What did I tell you? I don’t want anyone else. And if anything, God forbid, did happen to you where you got much worse, there’s no chance I’d hook up with someone else. So get healthy, you hear?” She can do less and less for herself over the next year. He has to feed her most of the time, hold the mug or straw to her mouth so she can drink, catheterize her four to five times a day because she has no control over her bladder and gets lots of urinary tract infections, turn her over on her side and back several times a night, force her out of bed at ten to ten-thirty in the morning, or else she’d sleep till noon or one. “Gwendolyn. Gwen. Come on, get up, open your eyes, you’re losing the entire day.” Don’t say anything to make her feel bad, he keeps telling himself. Don’t make things even worse for her. “I mean, you can do what you want, but I’d think you’d want to get up now, am I right?” She opens her eyes, looks at her watch on her wrist and says “But what am I doing? I can’t see these little numbers, even with my glasses. What time is it?” “Past ten,” and she says “Let me sleep another hour. I got to bed late.” “You got to bed around eleven, which is when you normally start conking out,” and she says “Please, twenty minutes longer. And give me a very tiny piece of Ambien so I can sleep, because I hardly got a wink in last night.” He usually says “No, I gave you more than enough last night, and since you snored half the night, you obviously got plenty of sleep. You get more Ambien, you’ll sleep till the afternoon.” She sometimes says “Don’t be such a dictator,” and he says “I’m not. I’m just doing what I think’s the right thing for you. I don’t want you to waste your life away in bed. And I know what you’re going to say. Okay, twenty minutes; no more,” and he leaves the room, reads or goes to his typewriter in the dining room, comes back half an hour later and changes her, exercises her legs and feet, swings her around and sits her up so her legs hang over the side of the bed and massages her shoulders and back and neck. Every other week or so—doesn’t want to do it more or else she’ll think he’s only massaging her for this—while she’s sitting up in bed and he’s massaging her, he drops his pants or takes his penis out of his fly and says “If you can, could you play with it while I work on you? I can use a little pleasure too.” She tries to, while he rubs her breasts under her nightshirt or continues massaging her, but she usually can’t grab hold of it, even after he wraps her hand around it, or she pulls it a little and then her hand slips off and she tries getting it back on or he does it for her. “It’s good exercise for your hands too,” he says, “right?” and she smiles and he kisses her head or bends her head back and kisses her lips and says “Anyway, for the time you were able to do it, it felt good.” Then he raises his pants or puts his penis back in his fly and massages her some more so she knows he did it as much as on the days he didn’t get her to play with him, and lifts her onto the wheeled commode and unlocks it and gets her into the bathroom. Once, after struggling to get her from the commode into the wheelchair, he says “I hate saying it but it seems to be getting increasingly hard for me to lift you. Maybe you’ve gotten a little heavier the last year, although you don’t look like you have…in fact, I bet you’ve even lost a few pounds. Or else it’s the dead weight of your body that’s making transferring you so hard…that you’re not helping me because you can’t.” “Use the Hoyer lift like the caregivers do,” and he says “And then what? I’m to spend ten to fifteen minutes getting you in and out of the lift sling seven to ten times a day? Who’s got time for it? And also, just turning you over in bed at night isn’t getting any easier either. Let’s face it, all that’s becoming harder for me because I’m getting weaker with age, no matter how much I work out at the Y, and I’m scared to think what it’s going to lead to. Dropping you on the floor, which is all we need, for how would I get you back up?” “The lift, if only you’d stop being so stubborn and learn how to use it,” and he says “You’ll teach me at the time, if anything like that does happen. But I’m worried, I can tell you, and you’ll also probably get hurt in the fall, and then there’ll be more to do and further complications. Oh, God, everything is going from bad to worse, when things are supposed to let up a little as I get older. I’m not supposed to have so many responsibilities. What a freaking mess to look forward to.” “Then put me in a nursing home and be done with it,” and he says “I don’t want to, would never want to, and besides, though this isn’t the reason I wouldn’t want to, we can’t afford it. We can afford twenty hours of caregivers a week, and the rest has to be left up to me. That’s all right, I don’t mind, and you’d be miserable in a nursing home, thoroughly depressed and bored, and deteriorate quickly rather than getting better or just staying the same as you are now.” “Please, you know I’m getting worse by the day,” and he says “You’re not; don’t say it. If you were, do you think I’d be so, I don’t know, calm about it?” and she says “Yes, as an act. But you give yourself away enough for me know what you really think.” “What I really think is that you’re getting better, and I selfishly say thank goodness to that, for in a few years I’ll be the one who’s sick and weak and you’ll be fully recovered and will have to take care of me,” and she says “What B.S.” “Look at her, my wife of almost twenty-five years; she called me a bullshit artist. Believe me, I would never fool you, baby; never.” “I pass.” About a month later, after he gets her into bed, she looks like she’s going to start crying, and he says “What’s wrong now? I was a little rough with you getting you on the bed?” and she says “No, you were fine; it’s just that there’s no sense to any of this.” “What do you mean?” and she says “Will you stop saying you don’t understand? What the hell do you think I’m referring to?” “Don’t yell at me. Not after all I do for you. Look, life isn’t so great for me either. I’m not comparing our situations, but there’s a lot of work for me to do and, in case you don’t know it, it gets frustrating and hard and a little tedious for me too.” “I’m sorry. You’re right. And I won’t disturb you anymore tonight. Please turn off my light and cover your shade. I want to go to sleep.” “Oh, boy, are you angry at me for what I said,” and she says “Not true. I’m only angry at my body. Please, the light.” A few weeks later, after he gets her ready for sleep and is about to get in bed himself, she says “Don’t get angry—please—but I’m afraid I need changing.” “What, ten minutes after I catheterized you? You’re just imagining it: you’ve done that before. Or you don’t want me to get any rest in bed, right?” And she says “Will you check?” He feels inside her diaper and says “Jesus, how did that happen? You’re so wet, I’ll have to change the towel and pads under you too.” “Could be you didn’t catheterize me long enough; sometimes you’re too much in a rush to get it over with,” and he says “I kept the catheter in till I saw a bubble go backwards in the tube. That’s always been the sign you’re done. What do I have to do from now on, catheterize you twice a night, one after the other? I’ve done enough tonight; I just want to get in bed and read.” “I’m sorry. If I could avoid this, I would,” and he says “Try harder to avoid it. Think; think. If you feel it coming, say so, goddamnit, and I’ll get you on the commode without you soaking the bed. I should really just let you lie there in your piss…I really should.” She starts crying. “Oh, there you go again,” he says. “Great, great.” He turns around, slaps his hand on the dresser and yells “Stop crying: stop it. Things are goddamn miserable enough.” She continues crying. Without looking at her, he says “I need a minute to myself, but don’t worry, I’ll eventually take care of you,” and goes into the kitchen and drinks a glass of water and feels like throwing the glass into the sink but puts it down and bangs the top of the washing machine with his fist and yells “God-all-fucking-mighty, what am I going to do with you? I wish you’d die, already, die, already, and leave me in fucking peace.” Then he thinks “Oh, no. I hope she didn’t hear me; it’s the worst thing I’ve ever said.” He stays there, looks out the window at the carport, has another glass of water and rinses the glass and puts it in the dish rack, turns the radio on to classical music and thinks “Ah, what the fuck’s the use?” and turns it off in about ten seconds and thinks “She still needs to be changed, so get it done and go to sleep,” and goes back and says “Okay, I’m here. A few minutes was all I needed. Tried listening to music to change my dumpy mood, but who the hell wants to listen to music.” She says “What you said out there—what you shouted—that is how you feel, isn’t it?” “What’d I say? I stubbed my toe in the kitchen on the door frame. That’s what happens when I think I can run around barefoot from one room to the other in the dark. So I said out loud—maybe yelled—‘Goddamnit,’ and other stuff, that’s all.” She says “You hoped that I die. Don’t try to get out of it. ‘Die, already,’ you said, ‘die.’ You could only have meant me.” “I never used the word ‘die.’ You’re hearing things. Besides, what makes you think you can hear clearly from this room to the kitchen? If I remember correctly, and this isn’t completely exact, I yelled ‘Goddamnit, you stupid fool,’ meaning myself; that I’m the fool. For banging my toe. But really the whole foot. It still hurts.” “You’re lying. You’re fed up with helping me, and who can blame you? You’ve done it longer than should be expected from anyone. Or else it’s become too much work for you because I’ve gotten much worse. But you should have told me calmly, not the sickening way you did, and then we could have worked something out to get other arrangements for me. I would have understood.” “No, you’re wrong,” and she says “Please change me and the towel before I pee some more and you get even angrier at me and maybe hit me instead of whatever you hit in the kitchen.” “I’d never do that to you; please don’t think there’s even a remote possibility of it. And try to believe I was only yelling at myself over the pain in my foot that nearly killed me. You know what the hell a stubbed toe’s like.” She looks away and shuts her eyes and he says “Oh, well, you’re never going to believe me tonight, but it’s the truth, I swear.” She still doesn’t look at him. “Okay,” and he changes her, gets the wet pads and towel out from under her and puts clean ones down, says “Which side you want?” and she points and he turns her on her side so she’s facing her end of the bed, covers her, says “Are you comfortable?” she doesn’t answer, “Is there anything more you want me to do?” with her eyes shut she shakes her head, he turns off their night table lights, dumps the wet pads and towel into the washing machine and thinks should he do a wash? Are there enough clothes in it for one now? Nah, save it for the morning, when there’ll probably be more wet pads and towels, and the noise might keep her up, and washes his hands in the kitchen and gets into bed. “Why don’t you sleep in one of the girls’ rooms tonight?” she says. “I don’t want to be in the same bed with someone who hates me and wants me dead.” “You’re being silly and a touch melodramatic, Gwen. I never in my life said or thought such a thing. I’m here to help you. I’d never say what you’re accusing me of because I’d never feel it even in my worst anger to you, which, by the way, I was to you a little before— angry—but nowhere near to the extent you said.” “Do what you want, then. But don’t try to touch me, and sleep as far from me as you can.” “Without falling off the bed, you mean. —Okay, no time for jokes. Anyway, now you’re really being punitive, keeping me from doing what I love most, snuggling up and holding you from behind in bed. But okay. Goodnight.” Doesn’t say anything or look at him. He gets on his back and thinks What the hell does he do now? Stupid idiot. If he had to say it, to get out some anger, why so loud? Now she’ll be like this for a couple of days no matter how much he apologizes. She heard. He only made it worse by trying to make her think she didn’t. Of course he doesn’t want her to die. She can’t believe he does. “Maybe I should sleep in one of the other rooms,” he says. “I want to do what you want. I don’t want my sleeping near you to make you feel even worse.” Waits for a response. None. “You asleep or just ignoring me?” Nothing. “Say something, will ya? You’re not giving me a chance. Isn’t it possible—isn’t it—that you might’ve misheard? —Listen, if you don’t say anything I’m going to assume you’re asleep and my presence here is no longer bothering you.” Just her breathing. She might be asleep. Good sign, if she is, that she wasn’t so disturbed by what he said that it kept her up. “I’d love for you to say, though I know you’re not going to, that you’re so unhappy, and not necessarily because of what you think I said, that you want me to hold you. And it’s not, you understand, that I want you to be unhappy just so I can hold and console you, by…okay. I better drop it. I’m getting myself in deeper, I think. I just have to hope I didn’t make you feel even lousier by what I just said. Put it down to my being dopey.” She hear him? By now he’s almost sure not. He yawns, thinks Good, he thought dozing off would be more difficult, shuts his eyes and is soon asleep. Wakes up about three hours later to turn her over on her other side, then around three hours later to the side she fell asleep on, then around two hours later on her back, which is what he does every night and at around the same time intervals, give or take an hour. From what he could make out in the dark, her eyes stayed shut all three times. It’s now six-thirty and he tries to sleep some more, can’t, dresses, does some stretching exercises in the living room, gets the newspapers from the driveway and reads one while he has coffee. Looks in on her at eight, just in case, although it’s early for her, she’s awake and wants to get up. She’s still sleeping on her back. Usually she snores a lot in that position, but he hasn’t heard any. He goes for a run—a short one, as he doesn’t like leaving her alone, asleep or awake, more than fifteen minutes—showers and shaves in the hallway bathroom, and a little after nine, right after he listens to the news headlines on the radio, he goes in to wake her, or else she might complain he let her sleep too long. What he doesn’t need, he thinks, is for her to get angry at him over something else, especially when she just might wake up feeling much better toward him. She’s surprised him a few times by doing that; mad as hell at him when she went to sleep and pleasant to him in the morning, where he didn’t think he even had to apologize to her for what he’d said the previous night. One of those times she even grabbed his penis in bed and pulled on it awhile without him having to ask her to. Then she got tired and stopped. “That was so nice,” he said. “I wish you had continued and there was more of that, not that I’m not satisfied with what I got,” and kissed her—tongue in mouth, the works, and she kissing him that way also for about a minute. Then he put her hand back on his penis, but she said “I can’t. No feeling left in that hand anymore, and the other one’s useless.” Anyway, best behavior today, okay? From now on, all days. Even to the point of being oversolicitous to her, because he has to take care of her better and wants to convince her that his bad moments and irrational outbursts are behind him. He just has to make a stronger effort, and keep to it, to make sure they are. Now he doesn’t know if he should wake her. Eyes shut, face peaceful, covers the way he arranged them when he turned her onto her back: top of the top sheet folded evenly over the quilt. “Gwen? Gwen, it’s me, the terrible husband. Only kidding. It’s past nine o’clock. Not a lot past, but I thought you might want to get up. You usually do around this time. If you want to sleep or rest in bed another fifteen minutes or so—anything you want—that’s all right with me too. I’ve got about fifteen minutes of things to do in the kitchen and then I’ll come back. Gwen?” One eye flutters for a moment but otherwise she doesn’t move. She normally would by now after that amount of his talking. At least open her eyes to little slits and maybe mutter something or nod or shake her head. “Are you asleep or falling back to sleep? Does that mean you didn’t sleep that well last night, although you seemed to have. I turned you over four times at night, more times than I usually do, and you didn’t seem to have wakened once.” Doesn’t give any sign she heard him. “I’ll let you sleep, then, half-hour at the most, because we both have to get started sometime,” and leaves the room, but a few steps past the door, thinks “No, something’s wrong; she’s too still and unresponsive,” and goes back and says louder “Gwen? Gwen?” and nudges her and then shakes her shoulder, moves her head from side to side on the pillow, puts his ear to her nostrils and throat and chest and then parts her lips and listens there. Knew she was breathing but wanted to see if there were any strange sounds. None; she’s breathing quietly and her heartbeat seems regular. But it might be another stroke, he thinks. This is how it was the second time; came into the room, couldn’t wake her up. Pulls her legs, pinches her cheeks and forearm, pushes back her fingers and toes, says “Gwen. Gwendolyn. Sweetheart. You have to get up.” Calls 911 and says he thinks his wife has had her third stoke. “Anyway, she isn’t responding.” While he waits for them to come, he kneels beside the bed and holds her hand and stares at her, hoping to see some reaction, then stands and puts his cheek to hers and says “I never meant any harm to you last night, I never did. I blew my top, but it was only out of frustration, all the work I do, one thing after the other, so exhaustion too. But I was such a fool. Please wake up, my darling, please,” and kisses her cheeks and then her eyelids and lips. They’re warm. That could be good. Straightens up, holds her hand and looks at her and thinks wouldn’t it be wonderful if her eyes popped open, or just slowly opened, but more to slits, and she smiled at him and said “I don’t hold anything against you. And I’m sorry if I frightened you. I was very tired and couldn’t even find the energy to open my eyes and speak,” and he said “I was so worried. I thought you had another stroke. I called 911. I’m not going to call them off. I want them to check you over, make sure you’re okay. That is, if you don’t mind. Oh, God, how could I have acted the way I did to you last night.” “Don’t again,” he’d hope she’d say. The emergency medical people ring the doorbell and he lets them in. He leads them to the back, tries to stay out of their way, thinks he didn’t hear a siren before they came. Maybe the absence of one’s a good sign too. By what he said on the phone, they didn’t think it that serious. No, there must be another reason for no siren. That there was one but they turned it off when they got to his quiet street because they no longer needed it. They work on her for about ten minutes, say she’s in a coma and they’re taking her to Emergency. He says “I’ll go with you, if it’s all right. If not, I’ll follow.” He thinks, as they wheel her out on a gurney, that if she dies he’ll never tell anyone what he said to her last night. That he took out of her whatever it was that was keeping her going. That he killed her, really. He holds her hand in the ambulance taking them to the hospital and says to the paramedic sitting next to him “If she doesn’t come out of this, then I killed her by telling her last night, when she was awake in bed, that she’d become too much for me and I hoped she’d die.” The woman says “Don’t worry, that wouldn’t do it, and she’s going to be just fine.” “You think so?” and she says “Sure; I’ve been at this a long time.” “She’s suffered another major stroke,” a doctor tells him in the hospital, “and because of her already weakened condition, I have to warn you—” and he says “Her chances of surviving are only so-so,” and the doctor says “Around there.” He calls his daughters, stays the night in the visitor’s lounge. She’s in a shared room in ICU and they won’t let him be with her after eleven o’clock. “Even for a minute?” and the head nurse says “I’m sure she wants you there. It’s the other patient who might be disturbed by your back-and-forths.” Next afternoon he’s feeling nauseated because he hasn’t eaten anything since he got to the hospital, and says to his daughters “I gotta get something in my stomach; I’m starving. I’ll be right back.”